Paul Annear shed-hunts on more than 400 acres in Richland County, Wisconsin, which is within the core area of the state’s chronic wasting disease zone. He’s never come across a sick deer, and he doesn’t find an unusual number of dead-heads. Based on anecdotal field data, it might seem like CWD isn’t a problem at all.

Instead, it is CWD testing of otherwise healthy-looking harvested deer that reveals the fatal syndrome: six of the last 11 bucks killed on Annear’s family land tested positive for CWD.

“As of late, the only sign of us having CWD is through the positive tests,” says Annear.

This is how CWD rolls. It is not dramatic or easily visible on the landscape. In fact, it’s not even noticeable in most infected deer, since the average deer can carry CWD for one to two years before outward signs of sickness appear. They are walking around with a 100 percent fatal neurodegenerative disease, shedding and spreading infectious prions to other deer for the entire incubation period. Yet to a hunter’s eye they appear healthy.

This makes CWD especially dangerous. It creeps below our radar and lulls many hunters into denial. When we detect a stench on a summer breeze or stumble on windrows of bloated deer carcasses piled up in a creek, we know it’s probably epizootic hemorrhagic disease, and we don’t have to be told it’s bad. The temporary deer losses to EHD can be high enough in some areas to warrant a bag-limit reduction that season. But CWD doesn’t show itself that way. It doesn’t strike rapidly and retreat. Instead, it slowly builds over time, and it doesn’t go away.

CWD vs. EHD

If EHD is a hornet nest in the shrub by your front door, CWD is the tunneling termite quietly eating your floor joists over the course of years. This contrast makes it easy for CWD deniers and apologists for the captive deer industry to use EHD as a red herring, a distraction from the fight against CWD. It is one of their signature tactics, and they’ve inspired many copycats who are quick to deploy this distraction in any online discussion. It’s an irrelevant argument. Just because the two diseases operate differently is no reason to treat either one of them less seriously.

The percentage of Annear’s family buck harvest that has tested positive in the last few hunting seasons (55 percent) is right in line with a subsection of the county where testing shows the CWD rate among adult bucks has climbed from near zero in 2008 to more than 50 percent in 2020. That same sub-sample of the county shows a lower rate among adult does, closer to 20 percent, and the Annears’ harvest reflects that as well.

“It’s interesting to note that we have yet to have a doe test positive,” says Annear, “and this year I shot a 5½- and a 6½-year-old doe according to the aging results that come back from Madison when you submit a deer for testing.”

Studies show adult bucks in CWD zones are twice as likely to carry the disease as adult does and younger bucks, a fact that probably results from the nature of buck behavior. Bucks congregate in summer in bachelor groups, share close quarters, and even groom each other regularly before spreading out over a wider landscape during the rut. Lower infection rates among females is a good thing for population stability, but those rates are climbing slowly in both sexes in states that are not actively trying to slow the spread of infection.

This matters when you’re dealing with a disease that causes infected deer to die at three to four times the annual mortality rate of healthy deer. A 2016 study of whitetails in Wyoming’s endemic area found CWD-positive deer were 4.5 times more likely to die annually than healthy deer. Few or none, though, will live long enough in the wild to reach the drooling, spraddle-legged, skin-and-bones stage seen in end-stage captive research animals. Instead, the slow but unseen damage to the nervous system makes infected deer more susceptible to other causes of death long before they look sick. They are hit by cars. They die of other diseases like pneumonia that healthy deer are better able to fight off. They fall to predators more easily. And they are more easily seen and killed by deer hunters. Annear witnessed exactly this with a buck he nicknamed “Thirsty.”

“I probably had over a thousand photos of this deer at a waterhole I installed in 2020,” Annear says. “I told my parents ‘I guarantee that buck has CWD.’ He appeared healthy, but something was just odd. He would show up at the waterhole at all times of the day. Sure enough, a neighbor killed it during gun season, and it tested positive. A buck he ran with all summer was a 3½-year-old my dad killed in early November, and it tested positive, too.”

Like Annear, hunters in other states have trouble “seeing” the impact of CWD other than in an e-mail containing test results. Dr. Allan Houston is a forestry research professor at 14,000-acre Ames Plantation, an ag research and education center of the University of Tennessee located in Fayette and Hardeman counties—the very counties where Tennessee discovered its first cases in 2018. Houston helps manage the long-running Ames Plantation Hunting Club, and he says 50 percent of the 2021 deer harvest tested positive.

“Curiously, even at this miserable rate, even with us here all year long, I don’t recall anyone ever seeing a deer in the classic CWD final stage,” Houston says. “It is even rare we can point to an animal on the slab and say ‘Yep, sick.’ But 50 percent of the time, they are sick.”

When a disease causes infected deer to die at three to four times the rate among healthy deer in the population, it’s like a pinhole leak in your truck tire. It’s like a thief stealing from you every day in amounts so small you don’t notice. EHD explodes randomly and recedes again, and deer populations recover. But with CWD, there comes a time after many years when the production of new animals isn’t enough to sustain disease losses plus the usual sources of mortality—especially hunter harvest.

CWD and Whitetail Management

Multiple scientific studies from the West, where CWD has been around longest in wild deer, have shown populations eventually begin declining as CWD grows in prevalence. Whether this happens sooner or later depends on the productivity of the herd, the amount of hunting pressure, and the countermeasures taken by wildlife agencies.

When will this happen in Wisconsin? No one can be sure. Disease prevalence is now reaching 60 percent and higher among adult bucks and 20 to 30 percent among does in the worst-hit pockets of certain counties in southwest Wisconsin. It may be a while yet before we know the long-term implications. However, we do know that CWD is always fatal, there is no cure, and there is currently no known way to get rid of it in areas where it is firmly established.

The good news is, other states that discovered CWD early enough are holding prevalence much lower through active management. Holding infection rates low means maintaining deer populations that can support hunter harvest for as long as CWD management activities continue. Illinois and Missouri, for example, have shown long-term success at flattening infection rates. Illinois, which found CWD along its Wisconsin border about the same time Wisconsin found it, has kept prevalence below 5 percent in most of its CWD zones. All testing in 2021 in Illinois revealed about 6 percent prevalence in adult bucks and 3 percent in adult does. In fact, this is a unique advantage in battling CWD: We are learning we can manage it if it’s discovered early enough. There is no managing EHD.

READ NEXT: Zombie Deer Disease: CWD’s Unfortunate Nickname

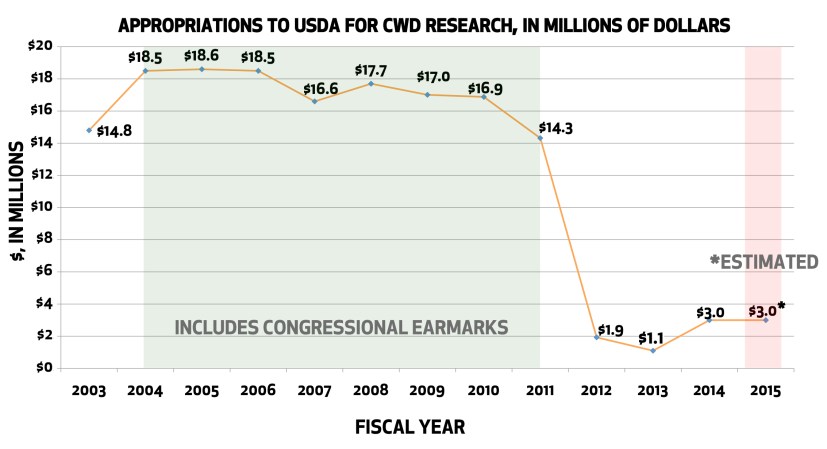

That’s what hunters in CWD-impacted areas can do: Rather than ignore CWD, support active management by the state wildlife agency and support legislation that would fund CWD management. Participate in the fight by submitting every harvested deer for testing so the extent and location of the outbreak are better known. Stop the spread by learning about local and state carcass-transportation rules, and dispose of all deer carcasses appropriately in the zone where they were killed. And, though there’s no evidence CWD has affected human health, doctors recommend you keep your personal risk as low as possible by waiting for test results before eating the venison of any deer or elk killed in a known CWD area.

CWD is neither harmless nor the doom of deer. There is an active fight against it, and the mission of hunters is to slow the spread of CWD in order to buy time for ongoing scientific research to find solutions. But first, we have to take this threat seriously. Don’t be deceived by the fact that you’re not finding CWD-killed deer scattered throughout the woods.