Our fascination with coyotes is undeniable. They can be aggressive predators, but also elusive prey. They’re considered varmints, but a late-season pelt from a mature coyote is a true trophy. And while coyote hunting may stir controversy in some corners of the country, the reality is that their numbers need to be managed just the same as the deer and elk that we so passionately pursue.

For many, coyotes are targets of opportunity, however true coyote hunters take their pusit seriously with specialized coyote hunting tactics and gear. Regardless of your skill level, hunting coyotes provides the avid outdoorsman year-round opportunities to hone their hunting craft and take an active role in predator management.

When done right, coyote hunting is also an adrenaline filled experience that will keep you coming back season after season. However, learning how to hunt coyotes does not come easy, and it requires a specific skill set to regularly coax a skittish coyote into a reasonable shooting distance. Tactics will vary depending on where and when you are hunting, but the basics remain the same. Below is a comprehensive breakdown of coyote hunting tips and tactics that I have used successfully many times over, plus a series of tips based on where in coyote country you plan to hunt. —Colton Heward

Finding Coyote Habitat

The coyote’s ability to adapt and expand are nearly unmatched with a distribution ranging from the high country of the Rocky Mountains, to the arid deserts of Mexico, to the humid everglades of Florida, and just about everywhere in between. However, there are certainly areas where greater numbers of coyotes will be concentrated.

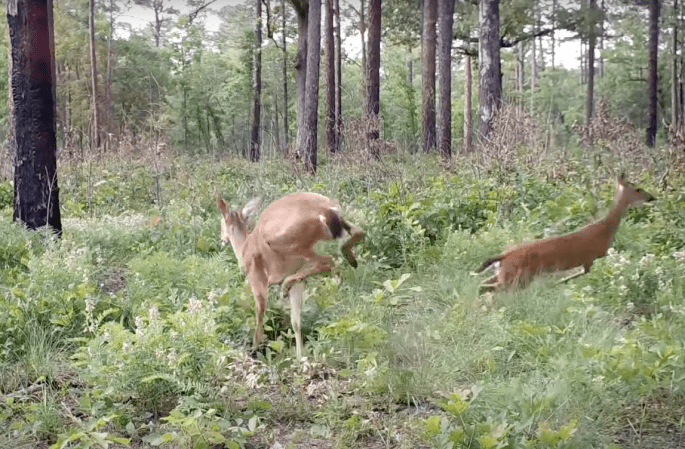

Every day is a game of survival for coyotes, constantly in search of their next meal. If you can find their food source, chances are there will be coyotes nearby. In most areas a coyote’s diet will consist primarily of mice and rabbits with the occasional deer when the right opportunity arises. Pay attention to areas where you notice a high concentration of prey and start your hunt there. If there is snow on the ground, you can also identify good areas to begin your hunt by

paying identifying tracks (of both coyotes and their prey). During the spring, coyotes will frequent deer birthing areas in search of an easy meal when does are dropping their fawns.

READ NEXT: Coyote Hunting Gear: Everything You Need to Get Started

Calling Coyotes

The most exhilarating way to hunt coyotes is by calling them into gun range. There’s something special about tricking the coyote into hunting you. This can be done using a variety of calls and tactics. Read our review of the best coyote calls here.

Locator Calls

Coyotes are often rightly referred to as “song dogs,” lighting up the night sky with a serenade of howls and barks. Howling is how they communicate each other’s locations. Hunters can take advantage of this natural habit to pinpoint a coyote’s whereabouts.

While coyotes will howl during daylight hours, they primarily howl at night or the first and last minutes of daylight.

When hunting coyotes, cover country in your vehicle before it gets light and let out a variety of coyote howls at various points atop a hill or ridge where sound will carry well. If after two or three howls you have not heard a response, keep moving. This tactic is similar to striking turkeys.

However, if you do get a response, mark the location you believe the howl is coming from. You can either wait

for daylight or continue on your search for more howls with a plan of attack to come back and hunt the area the howl came from later. Coyotes are active, but they are fairly territorial and will often be in the same general area day after day.

Distress Calling

Imitating animal distress calls does sound mildly morbid but is an extremely effective way to kill coyotes. Distress sounds signal an easy meal to all coyotes within earshot. Some coyotes will come in charging hard to the sound while others might tip-toe in circling down wind.

The type and variety of distress calls varies greatly from hand calls and reeds, to a variety of e-callers that run with a wireless remote, to even using the back of your hand to “squeak” one in. Calling coyotes sounds easy enough, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. Coyotes are extremely intelligent and can often separate the real deal from the man-made sounds of animals in distress.

Electronic calls (e-callers) have changed the game when it comes to calling predators with a plethora of life-like

sounds readily at your fingertips. While these sounds are great, there are several mistakes that people often make with them. First and foremost, the same sounds get played over and over by various hunters and coyotes become educated to these calls. Instead of coming for an easy meal, the coyote will turn and head the opposite direction. This often happens if that coyote was previously shot at and missed while investigating that particular sound. Use a variety of calls and do not be afraid to purchase after-market sounds that will separate you from the rest of the hunters.

The second mistake that is made with e-callers is the volume in which hunters play them. Do not set up your e-caller and max the volume out expecting to pull coyotes in from miles away. If you snuck into your stand and have the wind in your face, there is a chance that you’re within a couple hundred yards of a coyote. When you blast your e-caller on

maximum volume, you can bet that dog will tuck his tail between his legs and leave the county. Start your calling sequence at a low volume and work your way louder over time.

The type of distress calls you use will also vary depending on where and when you are calling. Rabbit distress calls are very effective when not overused and are the most common sounds just about anywhere you go. During the spring when coyotes have dens of pups, a pup distress call is incredibly effective. In my experience, these pup distress calls often ignite a fire under the coyotes who come charging into this sound looking for a fight. Be ready!

It is also worth noting that a variety of coyote howls and other vocalizations are very effective, especially during the winter months during their breeding season. I previously mentioned that howls are a great locator tool. The right howl from a lonely female coyote can also bring in potential suitors searching for a mate, or the dominant howl from an intruder can strike a nerve with a nearby coyote who will come in looking to maintain his dominance. When using coyote vocalizations, be cognizant of your surroundings as coyotes will often sit within eyesight of the sounds looking for a visual confirmation of what they are hearing before coming to the sound.

READ NEXT: How to Call Coyotes

Set the Perfect Stand

A common mistake that coyote hunters make is not thinking through their stand location. The right setup is just as important, if not more so than your calling sequence, when it comes to your success as a coyote hunter. Below are a few simple rules that will ensure you remain undetected by an incoming coyote.

- Always set up with the wind in your face. I know this sounds simple, but you’ll never outsmart a coyote’s nose.

- Set up with your back to a tree or bush to break up your outline and sit on the shady side of cover when possible. Coyotes have very good eyes and will quickly pick out something that does not blend into its surroundings.

- Always be sure your vehicle is out of sight from any potential angles a coyote might approach. I have often spotted a coyote coming from a distance only to have it stop and go the other way well out of shooting range. Upon further inspection, that busted hunt can often be blamed on the vehicle being seen by a coyote coming in from a high ridge or some other angle that was not accounted for.

- Know your surroundings. Before you ever start your calling sequence, range a variety of landmarks and make mental notes of their distance. Once a coyote is coming in, chances are you will not have time to range and shoot before the coyote picks you off and high tails it out of there.

- Do not set up right next to your e-caller. Coyotes have an uncanny ability to pinpoint where the noise is coming from even from several hundred yards away. If you are sitting right behind your e-caller, you are more likely to get picked off before a shot opportunity arises. I like to set up at least 30 to 40 yards from my e-caller and off to one side or the other from where I think the coyote will approach from to stay out of their line of sight.

- When possible, set up in an elevated position where you can easily survey your surroundings with minimal movement.

Coyote Calling Sequences

Now that you are set-up for the perfect stand and know what sounds you want to play or make, how long should you call for? The answer varies depending on who you ask, but at a bare minimum, give each stand 15 to 20 minutes before packing up and moving to the next stand. I like to start each stand with some sort of howl to perk the ears of any coyotes within ear-shot distance of the call.

After the initial two or three howls, I will sit in silence for a couple of minutes before making another coyote vocalization. The second vocalization will usually be a different howl or yip than the previous vocalization to make it sound like there are multiple coyotes in the vicinity. Sometimes I will even play this second sound again, allowing for two or three-minute breaks between each sequence. Finally, if these initial coyote vocalizations have not produced a coyote sighting, I will flip on some sort of distress call. This can be either a pup or prey distress sound, but leave this sound playing continuously. I will also usually start the distress sound at a low volume and gradually increase every couple of minutes. Imagine the first two coyote vocalizations as setting the bait and drawing the curious coyote closer, and the final distress sound setting the hook and hopefully bringing a wily coyote in on a string.

Coyote Hunting Guns and Loads

Coyotes are small and thin-skinned making them relatively easy to bring down with just about any rifle and cartridge of your choice. First and foremost, you want to be shooting a gun that you are comfortable with and have high confidence in its accuracy.

Popular cartridges amongst predator hunters include .223 Rem., 204 Ruger, and 22-250 Rem. for shots inside a couple hundred yards on up to the 243 Win. and the 6.5 Creedmoor for the coyotes that won’t fully commit and hold up several hundred yards from your setup.

One factor to take into consideration when choosing a coyote hunting rifle is whether or not you want to save the fur. If you are fur hunting, you will want to lean toward a smaller cartridge and select a bullet that does not implode on impact and put massive holes in the hide. On the flip side, if you do not plan on keeping the fur, a bullet that rapidly expands on impact, such as Hornady’s V-Max bullet, is perfect for killing coyotes quickly.

There is also a smaller niche of coyote hunters who will carry a shotgun with them to each stand to accompany their centerfire rifle. This is often useful when hunting coyotes in the woods. When coyotes are fired up, they will often come charging into the call with zero disregard to their surroundings. While I have not killed a coyote myself with a shotgun, I know many die-hard coyote hunters who claim there is nothing more exciting than rolling an incoming dog at your feet with a scatter gun. Inside of 30-yards any lead bird shot with a full choke will suffice. If the coyote is out there beyond 50-yards you will most likely need a OO Buck or tungsten load paired with a tight aftermarket choke tube to achieve terminal performance.

READ NEXT: Best Coyote Calibers

Other Coyote Hunting Gear

There’s a small handful of gear items, even above that of your weapon of choice and your calls, that will make you a better coyote hunter:

- A quality binocular and a capable rangefinder.

- A butt pad to keep your rear out of the mud and snow that is so common during predator hunts.

- Camo or earth-toned (or snow camo) clothing to blend in with cover.

- Warm baselayers to keep you warm so you avoid shivering.

- Read our full list of coyote hunting gear here.

Preserving Coyote Fur

If you intend to save the fur, removing it from the carcass is a little time consuming but a relatively easy process. Start by making a cut up the back of both hind legs meeting from both sides at the base of the tail. You can either cut the joint at the tail or split it to the tip, and then carefully peel the hide toward the head.

This method is referred to as “tubing” the hide and is the preferred method for most. At the feet, I like to cut the joints at the ankle and wrist bones and let the pros (my taxidermist) remove the remaining bones. Same with the head. If you are not comfortable caping the head, tube the hide up to the base of the skull and separate the carcass from there and let your taxidermist finish the rest.

If you skin the hide immediately after you kill a coyote the skin can nearly be peeled off without much use of a knife. If it gets cold and the skin sticks to the carcass, you will need to use a lot more knife strokes. As I mentioned before, they are very thin-skinned so be especially careful when skinning so that you do not put any additional holes in the hide.

READ NEXT: How to Clean a Coyote Hide in Your Washing Machine

Whether you are a veteran predator hunter or new to the sport, there are plenty of opportunities spread across every state in the union to get out and hunt coyotes. There is much more to learning how to hunt coyotes, and it takes years of trial and error to get good at it. But, heeding a few of the tips and tactics mentioned above will surely get you into the game and on your way to bagging more coyotes.

Coyote Hunting Tips Based on Habitat

Coyotes are out there waiting in habitat near you, and all you have to do is go after them to experience some of hunting’s knee-shakingest thrills with these coyote hunting tips.

While the basics of coyote hunting are simple—set up with visibility and minimize movement; keep the wind in your face or crossing; call in dogs by appealing to their stomach, territoriality, or libido—success hinges on the details. It pays to match your approach to the habitat, and assemble your gear with meticulous care. —Tom Carpenter

Coyote Hunting Tips for the Timber

Though traditionally thought of as creatures of the wide-open West, coyotes have moved into timber country in untold numbers in recent years. The challenges of coyote hunting expansive woods are clear: The cover never ends, and the calling noises you make with the coyote caller will only reach so far. Here are three solutions.

1. In flat country, search out clear-cuts, meadows, loggers’ landings, marsh edges, cover seams, and other openings, and set up there. You’ll gain much-needed visibility, your calls will carry farther, and you’ll be where the coyotes are—that combination of clearings, transition zones, and thick cover where prey (including cottontails, mice, voles, and moles) reside.

2. In hill country, head for hollows, gullies, valleys, draws, washes, and other terrain that lets you set up on one side and survey the opposite slope for approaching varmints.

3. In big timber habitat, set up often, call loudly, and wait a short time (15 to 20 minutes, with three to five distress calling sequences in there), then move on. Covering ground, and lots of it, is the way to find a coyote that will hear you; the dogs have many places to be, and call sounds do not carry far.

There’s another secret to shooting coyotes where the cover sprawls on forever: Scout hard. Here are three effective approaches. Spend a starlit winter evening out in hunting country, standing by your vehicle and listening for the yips, yowls, and howls of coyotes. Triangulate the approximate location of the calls (they carry better on a clear winter night) and you’ll know if there’s a pack in the area and where you might start your search.

An even better time to do this kind of scouting is the last hour before dawn, when the coyotes will be close to their denning area. It’s like listening for a turkey gobble to determine where his roost is. Hike in toward the howls, and hunt.

Or after a fresh snow, drive back roads and trails, and look for coyote tracks crossing. The purpose isn’t to take off and track the dog down (a formidable task), but rather to just know there are coyotes working the area.

Calling Strategies

Big woods are a good place to reach out with the volume that an electronic call provides. One of the best on the market is FoxPro’s Shockwave. Check out the FoxMotion, FoxPitch, FoxFusion, and FoxData features. And don’t let the word “fox” in the name fool you—this is a coyote-hunting tool with real power behind it.

Guns & Glass

By their very nature, big woods mean close-range shooting. This isn’t the place for long-range rifles and high-powered scopes. Rather, the best coyote gun in this situation is a shotgun to get on your target fast. Turkey shotguns make great predator guns because they feature short barrels that are easy to hold and aim, and tight chokes. For under $300, the rugged Stevens Model 320 Turkey Gun in 12-gauge sets you up for dual-season action.

You’ll be just fine with open sights. But if you like optics, couple the 320 with Weaver’s Rapid Fire Red Dot Sight, which will get you on that dog quickly and aiming fast.

Decoy Tips

With its adjustable speeds, the Primos Sit N Spin Crazy Critter coyote decoy offers both erratic movements and a real rabbit look.

Coyote Hunting Tips for Farmland

After exurban and suburban areas, agricultural habitat has experienced the biggest increase in coyote populations over the last decade. That doesn’t mean farmland song dogs are easy to hunt. On the contrary: These coyotes are pressured and persecuted hard by everybody and their uncle. Folks who hear the dogs howling at night know where they live and pursue them with a vengeance—and educate them in the ways of hunters.

Here’s another challenge: Agricultural coyote habitat varies widely. Rolling dairy farm country with a mix of woodlots, row-crop country punctuated with sloughs and grasslands, beef country with its expansive pastures and extensive wooded river bottoms—they’re all different, and no single setup and approach fits all. As a hunter, you have to be as adaptable as the coyotes you’re chasing.

All these landscapes have two things in common, though: limited cover, and ample open areas across which to draw curious coyotes. The trick is getting in unseen with the wind blowing from likely coyote hideouts toward you, setting up secretively, calling with a purpose, and staying patient with these suspicious and reluctant canines.

Don’t overestimate the amount of cover a coyote needs. Where I hunt coyotes in western Minnesota, frozen cattail sloughs serve as the hideout of choice. In the southern Wisconsin dairy farm country where I grew up, brushy abandoned pastures harbor higher densities of coyotes than do traditional woodlots.

Never underestimate the wariness of farmland coyotes. They may be used to vehicles driving around, but not yours; sneak in on foot. Farmland parcels can be small, with only a limited area or two for setups. If the wind is wrong, hold off and hunt the area another day rather than educate the coyotes even more.

Set up across fields, pastures, or meadows, and call into cover—grasslands, wetlands, fence lines, brushy thickets, forgotten orchards, fallow meadows, ditches, and other spots where prey (rabbits, pheasants, quail, mice) hide out and coyotes would be prowling. Keep the wind blowing from the cover to you, or flowing cross-lots, and draw the coyotes out.

Calling Strategies

Fat farmland coyotes need big sound to get their attention, and some finessing to get them to commit. You can do both jobs with one call. Primos’ Raspy Coaxer (1) creates long-range prey screams to get things started. Then, by covering one port with your finger, you can make little whines and whimpers.

Some farmland coyotes have heard it all when it comes to rabbit-in-distress sounds. That’s when you need to appeal to their territoriality or (late in winter) their sex drive.

Carver Predator Calls’ Big Dog Howler and Pup and Female Howlers are hand-carved, human-tuned calls that are ready to make the coyote sounds you need.

Guns & Glass

A coyote gun that’s smaller than your deer gun is more fun—and more palatable to landowners. Let’s go all-in for a rifle under $1,000 while we’re at it.The Savage Model 25 Walking Varminter carries a budget-friendly price but performs like a much more expensive rifle. And it comes in one of the perfect small-centerfire coyote calibers, the .22 Hornet.

Bushnell’s Trophy 3–9×40 is bright, lightweight (to go with the rifle), and affordable.

Decoy Tips

The Mojo Critter coyote decoy is lightweight, simple to use, and operates on four AA batteries. It’ll give that coyote something interesting to focus on instead of you.

Coyote Hunting Tips for Open Country

Classic coyote hunting begins west of the 100th meridian. Every serious coyote hunter owes it to himself to hunt coyotes out where the deer and the antelope play. You can have more action here in three or four days than you can generate in an entire season elsewhere.That brings up another important point: The West is a perfect place for a new predator hunter to gain experience and gut-level confidence, knowing that coyotes really can be called in. With high populations of coyotes, there’s always more opportunity awaiting if you commit mistakes on your call or miss with your rifle.

But don’t get the wrong idea. One of the worst miscues you can make with Western coyotes is being overconfident and nonchalant. These varmints are ready to beat you up. All that open country both helps and hurts: You can see coyotes coming from a long way off and be ready for them, but those dogs can spot you in a heartbeat if you’re silhouetted or making sudden movements.

So be a real sneak as you move about or travel between setups. This means skirting below the crests of ridges and hills, and never skylining yourself. Only cross heights at dips or saddles. And for heaven’s sake, don’t stand on a hilltop and glass.

When moving into a likely spot for a setup, stay low, be silent, and slide in quietly. Treat the situation like a coyote is within a hundred yards—because he might be.

Five Prime Setup Spots for Western Coyotes

- Within sight of a rocky bank, jumble, ridge, or escarpment.

- Just beyond cedar thickets, willow tangles, and other daytime coyote hideaways.

- In river-bottom habitat that’s patched with brush and meadows.

- In rolling pastures of low sagebrush or other shrubs.

- Anywhere the terrain is broken and inhospitable.

Believe it or not, many ranchers welcome responsible predator hunters. Get landowner contacts from local chambers of commerce or cattlemen’s associations. Most landowners are only too happy of get rid of a few coyotes in winter, when the cows are in feedlots.

The West also offers ample Bureau of Land Management (BLM) acreage, much of which is open rangeland and prime for coyotes. The best way to get maps: Go to blm.gov, click on “Offices/Centers,” and contact the state office for the area you want to hunt.

Calling Strategies

Sometimes you need to “match the hatch.” Western coyotes love chowing down on a big old jackrabbit, and the Jack Rabbit Distress call from Bugling Bull provides deep-throated, slower squalls that mimic a jack in trouble.

Wide-open country begs for electronic callers that can really reach out and do the work for you. Primos’ Dog Catcher (which you can operate via remote control from up to 150 yards away) comes preprogrammed with 10 sounds, and allows you to play two sounds at once.

Guns & Glass

Part of the allure of Western coyotes is the chance to take them at long range. For that, you need a rifle that reaches out fast, shoots flat, and hits where you point it. You could spend $10,000 on that gun, or you could spend around $1,500. Let’s consider the latter.

It’s hard to beat Tikka for value and accuracy, and the Tikka T3x Varmint comes in at under a grand to boot. A free-floating barrel benefits accuracy. It comes in both .22/250 Rem. and .223 Rem, and now 6.5 Creedmoor. I prefer the .22/250, which shoots a bit flatter and faster than the .223 Rem.

For glass, go with the Leupold VX-2 4-12x40mm. Leupold offers the clearest glass and reliability for the price.

Decoy Tips

The windy West is the perfect place to go low tech: Tie a feather to a stake or twig and let it fluff, ruffle, and blow in the breeze (5).

Coyote Hunting Tips for the Suburbs

Proof positive of the coyote’s incredible adaptability is its foothold in exurban and suburban areas, sometimes within sight of city skylines. It’s hard to find a community anywhere across the country that doesn’t have a coyote problem in its outlying areas. You can be part of the solution.

The good news is that suburban coyotes are underhunted. The bad news is, they’re largely on private land. Sometimes that’s the chief trick for suburban predator hunting—just getting access. To do this, you need to make a public-relations play. Knock on doors in neat street clothes (not your hunting camo) and explain your interest in hunting coyotes and taking a few of them off the neighborhood’s hands. Leave a card identifying yourself.

You’ll be surprised at how many landowners are willing to let you in, especially if you talk a lot about gun safety. Promise to refrain from using a high-powered rifle. Instead, stick with shotguns, rimfires, or light calibers like the .17 Rem. and .22 Hornet. And if a landowner has reservations about even those firearms, offer to use the best crossbow or (better yet) a high-powered airgun.

Once you’re hunting, stay under the radar to prevent encounters with folks who might be driving, biking, walking, or jogging along roads or trails.

Hunting only at dawn and dusk solves some of these issues, and those are good times for coyote activity anyway. Another trick is to hunt populated suburban and exurban areas only on weekdays, when fewer people are about. That’s a lot about PR, but you won’t be doing much suburban hunting without it.

Once you’re in the field, hunting city-cousin coyotes takes on a few twists. These dogs are highly opportunistic and often quite competitive with one another, so they are usually going to come in fast to rabbit and other distress calls. If a coyote comes in and you shoot it, stay put for five minutes and call again; there might be another dog in the vicinity. Property lines can be tight in these areas, so hone your skills with squeaker calls in case you need to coax a coyote through a fence or across a road and onto land where you have permission to hunt and shoot.

RELATED: The 7 Best Predator Mouth Calls

Calling Strategies

When a smart citified coyote gets coy on you, you have to give him a little bit of soft love. With a little finesse from your fingers, Knight & Hale’s Mouse Squeaker makes the irresistible little pleadings you need to lure that dog a few steps more. ($10)

The suburban predator hunter needs versatility in his arsenal, and a mouth call such as the Primos Hot Dog has it. You can make coyote yips and howls when the mouthpiece is attached, or remove the mouthpiece and make distress calls imitating birds, cottontails, squirrels, and fawns.

Guns & Glass

Pyramyd Air’s Dragon Claw is a .50-caliber pneumatic air rifle that throws a 225-grain projectile at 679 feet per second with 230 foot-pounds of energy. That’s plenty of punch to take down a coyote at 50 yards. As an added benefit, there’s no noise to call attention to you.

For less than $200, the Leapers UTG Accushot 1–8×28 scope pairs well with the Dragon Claw. The low magnification is perfect for closer-in suburban hunting situations.

Decoy Tips

Western Rivers’ Deceptor Rabbit coyote decoy looks like the real thing, can be used on a stake or on the ground, and is remote-capable.