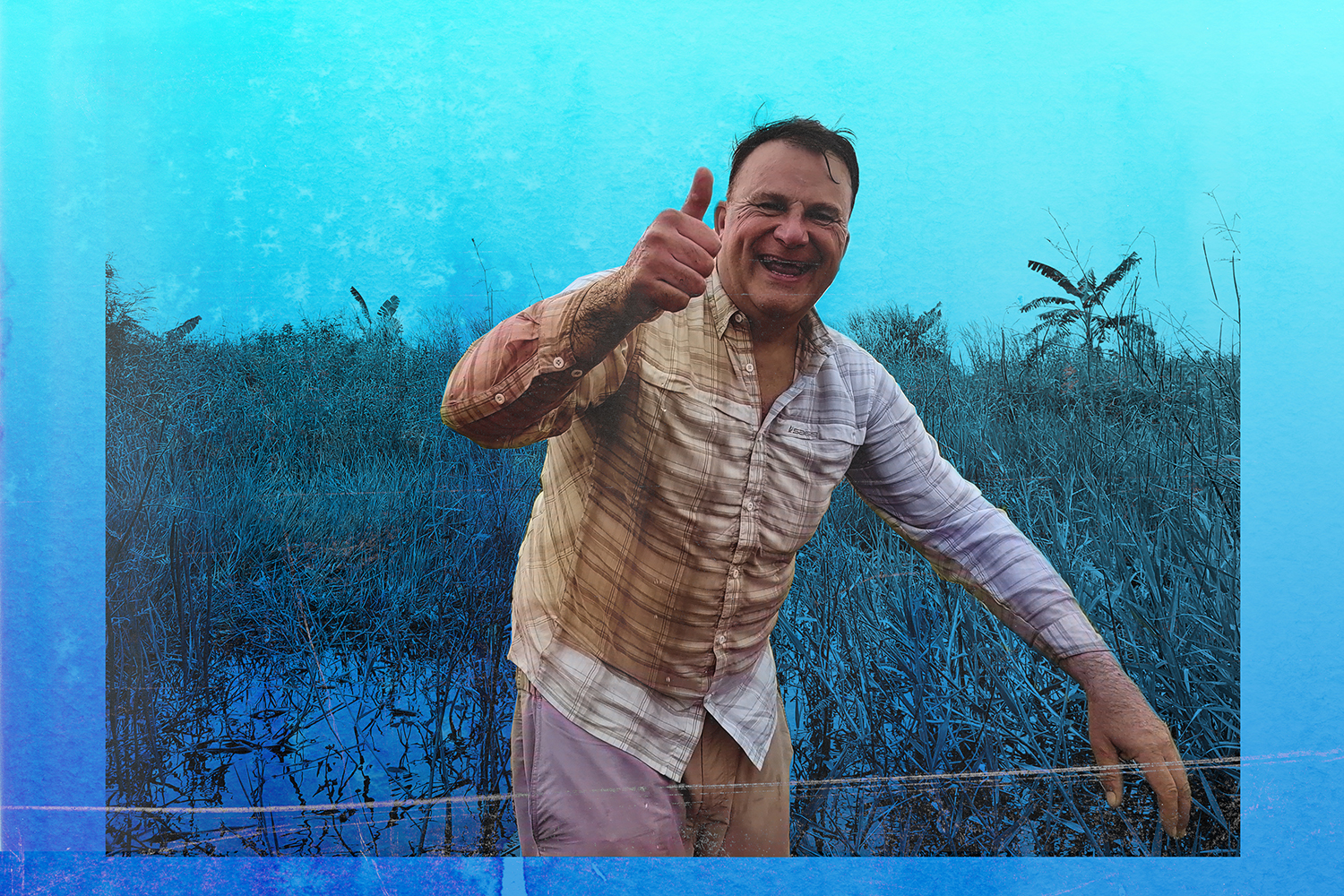

THE SWELTERING HUMIDITY of Thailand seeps into Rich Hart’s every pore as he contemplates what he has just accomplished. The jet lag, flesh-eating bacteria, and dehydration that Hart suffered to get here don’t matter in this moment. What matters is that he’s standing knee-deep in a river, holding a fat snakehead in full spawning colors. Purple and green shine through its dappled, striped flanks.

After weighing the fish with certified grips—14 pounds 2 ounces—he holds out the snakehead again for a final photo. There’s not much danger to the air-breathing river-dweller, so one more snapshot seems appropriate before letting his world-record fish swim away.

Then Hart washes the slime off his hands in the muddy river, and makes another cast.

The Traveler

“Everything in the jungle wants to kill you,” says Hart in his breakneck British accent. “But it’s the smallest things that end up getting you.”

But to chase world records, you have to steel yourself for obstacles and competition. Record chasing is the sum of equal parts obsession, the desire to know more about the fish that occupy your mind, and at least enough ego to want your name inscribed in the record books. Anglers who seek world records do so at the expense of many things, including their time, money, health, and work. Some record chasers are solitary. Others build lasting relationships with fellow fanatics, be they buddies, guides, or locals.

For his part, Hart chases records for as many species as possible, but he cherishes the snakehead above all. That 14-pound snakehead was indeed a world record—on 12-pound tippet.

While many fishermen’s eyes might glaze over at the mention of tippets, Hart’s light up. The International Game Fish Association has created detailed rules for line class and tippet class records, with “tippet” being the preferred term among fly fishermen for the smallest diameter line connecting the fly to the leader. Most anglers know about the 22-pound 4-ounce world-record largemouth bass at the top of the IGFA record book (actually, there are two). Many don’t realize there are 14 tippet records for largemouths, three of which are currently vacant. These records have become the stuff of obsession among those, like Hart, who strive for the best fish in a particular tippet class.

In his 10 years of chasing records, Hart has accumulated an impressive 114 IGFA record entries (34 of which still hold as of this writing). He began focusing on record fish while under the influence of Jean-Francois Helias, himself an IGFA legend with 116 total records covering little-known Southeast Asian species like the beguiling arowana and the yellow-streaked snapper. Helias runs a successful outfitting business in Thailand and has made a career guiding clients like Hart into wild places.

He’s interested in the biggest, nastiest fish he can find, which often leads him to hard-fighting fish in hard-to-reach places. That’s where lighter and lighter tippets come into play: The lighter the tippet, the harder the fight. And Hart is looking for a fight.

Hart also holds the Guinness World Record for the heaviest freshwater fish ever caught on a fly.

“I spent a month in Guyana trying to find that fish,” he says of the 415-pound arapaima, a mammoth tropical species that resembles a bowfin. But he’s spent the most time and money chasing snakeheads, which are native to Southeast Asia. The fish Hart considers “the smartest on earth” prefers mucky water and can even breathe oxygen out of water. There was an intense fear in the United States when it was accidentally introduced to the Potomac River system in 2004. Now the snakehead has become a popular game fish in the U.S. But for Hart, it’s best to chase them on their own turf.

The Lightweights

The all-tackle IGFA striped bass world record is an 81-pound 11-ounce monster caught on an eel and rattle in August 2011. That record will probably never be broken because the overwhelming majority of bass that size have disappeared from striper fisheries. It’s one of the great tragedies of the Northeast: Striped bass were coaxed back from the brink of extinction only to be nearly wiped out once again.

That’s partly why Ron Mazzarella decided to think small. The investment specialist from New Jersey decided he would hunt for the 2-pound tippet record. In order to catch a striper of any size on 2-pound tippet, you have to use a tiny fly and a modified trout rod. So Mazzarella’s desire to fight a fish as ornery as a striped bass on 2-pound tippet seemed like a fool’s errand.

To aid him on his quest, he enlisted the help of Paul Dixon, a chameleon in the fly-fishing world. Dixon has been everywhere, met everyone, and seen nearly everything. He’s also one of the most talented tarpon and striper guides on the Eastern Seaboard.

“My buddy’s eyes rolled back in his head, and so did Paul’s,” Mazzarella says of the sloppy morning in November 2005 when he told them he wanted to chase the 2-pound record.

It was pouring rain that day, and Mazzarella was using a 10-foot 4-weight rod and a Rhody Flatwing. Their boat was the only one off Montauk Point. They had agreed that they didn’t want to kill the fish, so they had the live well prepared and a marina with a certified scale on standby. They came across a bass boil in a shallow cove, and Mazzarella took his shot. The ensuing fight taxed his tackle, but eventually Mazzarella fought the fish close to the boat.

“Paul, do you have a gaff?” Mazzarella asked.

“Paul, do you have a net?”

“No.”

Dixon scrambled for something useful and turned up his old BogaGrip. Lipping the fish, he told Ron, “There’s your new world record.”

The pair made a mad dash to the marina and secured the striper’s weight at 19 pounds even. They released the fish in the harbor, and that was that. They had done it.

Mazzarella wanted to catch the biggest fish in the most challenging way possible—a backward-sounding strategy that’s oddly common. Legendary tarpon angler and IGFA board member Andy Mill once told me, “We do this because we want to make it harder. When you’re record fishing, the hunt becomes exponentially harder.”

Mazzarella’s record has stood since 2005 partly because no one else has been able to catch and land a nearly 20-pound striper with a rod and setup designed for a 2-pound trout. But it’s also partly because not than many anglers are trying to break it. He’s now turned his attention to the 6-pound-tippet-class record.

The Number Cruncher

Mosquitoes hum overhead as Meredith McCord stands ready on the bow of a flats skiff with a crab fly in her hand. The boat idles in the skinny water of the Louisiana marsh. Fifty feet of line is coiled neatly at her feet because she knows she’ll have only a half second to think once she spots a tailing redfish nosing through the mud looking for dinner.

When the signature spotted tail emerges from the brackish water, she waits. Holds a breath. Then McCord fires the fly toward the bank with a perfect loop.

Two strips and the water explodes. This red won’t break her current record, but it’s one more catch on her preparation checklist to break her own 2-pound redfish tippet record of 18 pounds 1 ounce.

McCord has 233 IGFA records, with 114 currently holding. If you want to learn some complexities about how to land a variety of fish on a light tippet, then she’s your gal.

“The reason I chase records is to become a better angler,” says McCord. “It’s an intense competition with myself.”

This is a common theme among many obsessive record chasers. Anglers who fixate on records aren’t necessarily trying to conquer the fish they’re chasing. Instead, it’s a very specific means of self-improvement. And not an easy one, either.

“Record fishing is work,” McCord admits freely. “I’ve had a lot of success, but a lot of defeat.”

She keeps meticulous track of her records. She can rattle off her average fight time (under four minutes) and how many of her record fish she’s released (98 percent).

McCord’s chase came from a promise to her dying father that she would catch 100 world records just for him. He passed when she was still at number 78. On Father’s Day in 2016, however, she landed No. 100—on her family farm in Texas.

“Out of all of them, that hundredth is the most special,” she says. That hundredth was a largemouth caught in a pond where her father had taught her to fish.

The Secret Keeper

Watching someone tie a complicated knot like the Bimini twist on YouTube gives you a perverse sense of overconfidence. I can do this, you think. I am a champion who will catch the next IGFA record on my amazing, unbreakable knot. Let’s go fishing.

The inevitable bird’s nest of the first few failed Biminis brings you back to reality quick enough. The knot helps protect delicate tippets from the inevitable wrenching of a big fish, but you need three hands to tie it. That’s why Spencer McCormack of northern Michigan has never messed with the complex tippet-saving, spring-loaded Bimini.

“I just use double surgeon’s knots,” McCormack says to me with a laugh. Even without the Bimini, the 36-year-old has managed to land and certify three IGFA smallmouth bass records using patience and finesse—and a scientific approach.

“I just released a fish that I’m certifying right before we started talking,” he says with a modest grin from an undisclosed location at the tip of the Michigan mitten. He’s sitting at a picnic table, and I can see a Key West skiff beached behind him. He squeezed in a morning of fishing before heading to his job as an environmental specialist for the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians. “Six pounds 7 ounces on 12-pound tippet.”

Twelve-pound tippet would be the rough equivalent of a standard largemouth setup on spin tackle. Anyone who’s ever chased Larry knows that a 6-pounder on any setup is an achievement.

Sheer curiosity led to McCormack’s quest for world records.

“I had these amazing fish right in my figurative backyard, so I started trying to test myself,” he says, remembering when he began to study his water in earnest about 10 years ago. He was already taking measurements for his work in fisheries sciences, and those observations grew to include his personal fishing. Now McCormack moves with the water temperature, stalking bass as they move farther into the shallows before the spawn.

Not content to simply dredge the bottom with heavy flies, McCormack studied insect patterns and built a Gurgler-style fly that mimics a combination Hexagenia mayfly and dragonfly to catch bronzebacks in skinny water on the surface.

This might sound overly complicated to the uninitiated. But when he threw that custom fly, McCormack says, “It was like getting struck by lightning.”

Things took off from there, and he became obsessed with dialing in the movement of bass through smaller lakes and eventually out into Lake Michigan. Now, instead of just fishing for smallmouths like he used to, McCormack learns what he can from each fish and applies these lessons to the next one.

McCormack is a quiet fisherman with the easy manner and self-awareness of someone content with where he’s been and where he’s going. Where he’s been, exactly, I have no idea, because the honey holes in the north country are reserved for those willing to make the trek from Traverse City to seek out the glacial lakes where smallmouths grow to the size of lap dogs. Where he’s going, exactly, I have no idea. Because McCormack, like every record chaser, knows to never, ever burn the next spot.

This story originally ran in the Diehards issue of Outdoor Life. Read more OL+ stories.