We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

It’s the goal of many clay shooters and bird hunters to one day own a custom break-action smoothbore, thus the bespoke shotgun has long been a coveted item for shooting sports enthusiasts and wingshooters alike. Some of the most well-built side-by-sides and over/unders are crafted by gunsmiths in Italy, Belgium, France, Germany, and England. But it is the British, specifically the gun houses of London, that have engineered the finest bespoke double guns in the world. Firms such as Purdey & Sons, Holland & Holland, Atkin, Grant, and Lang, W.W. Greener, and Boss & Co. have been constructing bespoke smoothbores for over 200 years. These guns are hand-crafted, detailed, and expensive—the cost of a British-made double can exceed $250,000. In the world of custom shotgunmakers, they are known as “London Bests,” setting the standard that every other manufacturer of bespoke shotguns strives to live up to.

The Rise of Driven Hunts and Bespoke Shotguns

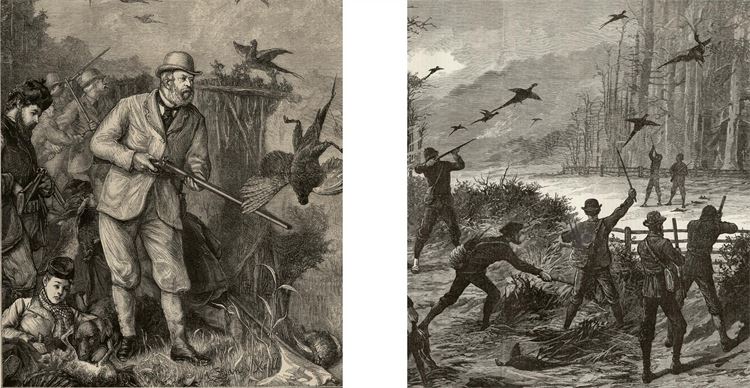

British gunsmith Joseph Manton (1766 – 1835) is credited with evolving flintlock shotguns into side-by-sides, giving form to the modern double gun, which has seen little change since Manton’s design improvements. Famed gunmakers James Purdey, Thomas Boss, William Greener, and Charles Lancaster all worked for him. Projectile ignition began with flint, then percussion cap, and finally the advent of self-contained cartridges. By 1870, breech-loaders capable of shooting centerfire cartridges were commonplace. As a result, the sport of shooting driven game flourished among Great Britain’s aristocracy, its biggest proponent being Edward, Prince of Wales, the son of Queen Victoria.

The queen had little faith in Edward’s ability to rule. His mother’s misgivings left the prince free to pursue his own interests, one of which was shooting side-by-side shotguns. Edward bought an estate in Norfolk dedicated to driven pheasant and partridge shoots, inviting nobles to join his hunts. The sport took off among England’s elite. Gamekeepers were employed to keep stocks of pheasant and partridge plentiful (it was common for 500 to 1,000 birds to be shot during driven hunts). A circuit of driven pheasant shoots for noblemen with stops around the United Kingdom soon followed. Edward was an avid participant and promoter of them all until his death in 1910, eight years after he was crowned king. Driven hunt popularity begat a boom of bespoke shotgun sales. Afterall, a noble hunter had to have a fashionable (well-made and expensive) firearm to shoot his quarry.

Two centuries later, there remains a strong market for custom smoothbores. Many of the London shooting houses that were founded in the early 1800s continue to produce bespoke shotguns for those of financial means.

The Boss: Britain’s First Successful Over/Under

Traditionally, shooting with anything other than a side-by-side was considered gauche, but now bespoke over/under shotguns, which have been in production longer than side-by-sides, are common. The bastion of over/under design is in Italy with Fabri, Perazzi, Beretta, and others leading the charge, but the over/under was born in Britain. Boss & Co. built the first highly successful over/under (it was not the first o/u, however). Patented in 1909, the Boss used trunnions or round projections in the action that mated with cutouts on the breech of the barrels to form the hinge. Projecting bites extended from the face of the breech, making for a slim action at lock up. This same locking system is now used in guns built by Perazzi and Beretta.

Building Early Bespoke Shotguns

Modern bespoke gunmakers mostly build their custom smoothbores completely in house. But up until the 1960s, gunmaking was largely a cottage industry. Shooting houses farmed out the work to different gunsmiths and craftsmen with specific skill sets. Then the gun would be refined and assembled at the home factory.

My own 19th century Henry Atkin from Purdey is an example of how guns were built in that era. Made in 1895, the sidelocks were engineered by Joseph Brazier, a premier lock maker of that time period. The barrels were built by “strikers,” men who profiled the outside of the steel tubes. It then went to a barrel borer, who reamed and smoothed the internal bore, leaving sufficient room for fixed choke adjustment. A walnut stock was shaped and trimmed for fit. Once all the parts were made and delivered to the parent firm, the gun was put together.

Fitting the Bespoke Shotgun to the Shooter

Buying a bespoke shotgun is much like purchasing a fine tailored suit. Every dimension of the shooter is measured, including the size of their hands, arm length, height and weight, eye dominance, and the kind of shooting for which the gun is intended. They are taken to the gun maker’s shooting grounds where an adjustable “try gun” is fired under the watchful eye of a skilled fitter to establish the exact stock dimensions for that person. The shooter will often start at the patternboard so the fitter can get an initial impression of how the gun needs to fit. Then the shooter moves to different stands where a sequence of clay targets are thrown. The fitter gathers all this information and passes it on to the stocker, who builds the custom stock.

The Gunmaking Process

When my Henry Atkin was made, the actioner began with a block of steel, using hand tools to craft the action. Countless hours were spent chipping away the extra metal and building the 55 individual parts (there are many more pins and screws) needed for a sidelock to function properly. It must have been an excruciating process.

CNC and CAD machines are now relied upon to perform the bulk of this work. It was controversial when gun makers started using them, but the quality of bespoke shotguns has not suffered, and the machines speed up the gun-making process. Today, the actioner can clean up any imperfections left behind by the machines so the jointer can marry the barrels to the action.

When fitting the gun parts, a craftsman keeps an oil lamp lit, the smoke from which is applied to the metalwork. When the black from the smoke is worn off in the fitting process, more metal is removed, the parts are re-blackened with smoke, fitted, worked, and filed again. The procedure is repeated until the fit is perfect: “To the thickness of smoke.”

Initially most bespoke barrels are machined to within thousandths of an inch, then hand-filed for centricity. Barrels are lapped—a process that removes any inconsistencies in the bore, so the gun shoots accurate—using a cradle and polished lengthwise with a lead lap coated in abrasives. Modern shotugn barrels now come with interchangeable choke tubes that produce wider or more tightly constricted patterns. But a bespoke gun—in its truest form—has the bores choked to the pattern percentages desired by the customer. For example, driven hunt shotguns are often regulated to shoot high as most shots are on birds flying overhead. For hunting in the states, called “rough shooting” by the English, the barrels are typically regulated to shoot 50/50 or a slightly higher 60/40 pattern.

Case-Hardening Bespoke Shotguns

Case hardening is often applied to the action and locks of bespoke shotguns. True case hardening, which hardens metal at the surface for added durability, involves packing the cleaned parts into an iron box filled with charcoal, leather, and bits of other substances kept as trade secrets. The box is then heated to an extremely high temperature and kept there for a precise amount of time. Then the contents are dumped into a cold-water bath.

A century ago, the shooting houses did not have the advanced technology they enjoy today, so it was difficult to keep temperatures consistent during the heating process. During hardening various components often warped and the skill of a seasoned hard fitter was required to make pieces fit during final assembly.

Bespoke gun houses also employ engravers, so you can customize your shotgun further. For example, Purdey is known for its rose and scroll work included it in the price of their bespoke guns. But if you want game scene engravings or gold inlays, they will accommodate you.

How Long Do You Have to Wait for a Bespoke Shotgun?

A bespoke shotgun typically takes two to four years to complete. Even when all the components are ready for assembly, it still takes around 75 hours—spaced over a few months—to put the gun together. The gun must be proof tested as well to ensure it is safe to fire (an outside agency like the London Proof House does that), and then the finisher takes the gun to the company shooting grounds for a thorough field test.

The only way the time frame can be sped up is if the gunmaker has a shotgun that was in the process of being made for another buyer that did not take possession of it (and you share similar measurements with that person). Not to be morbid, but the most common occurrence is when an older buyer passes away before the shotgun can be finished—it happens more than you think. Though unfortunate, this gives someone else the chance to step in and purchase the gun. Recently, many of the firms have begun making guns with stock dimensions for average size shooters. The fit can be fine-tuned for a customer in a hurry.

Read Next: The Biggest Shotguns of All Time

Buying a Bargain Bespoke Shotgun

There is an active used market for bespoke shotguns, specifically at gun auctions, which is one of the few ways for us common folks to obtain an affordable British double. If you buy a second-hand bespoke shotgun many of the workbooks of the great gun makers are still in possession of the manufacturers and historical societies in London. For a small fee, you can often find out for whom your gun was made along with the original specifications.

Owning and shooting one of these guns is a special pleasure—I have certainly enjoyed taking my Atkin afield. Just know that most British shotguns are chambered for 2½-inch shells, which are not widely available in the U.S., except in .410-bore. RST and some other ammo makers have periodic runs of the shells for the other gauges, but it’s sparsely done, so handloading will be your best bet. A MEC 600JR coupled with a MEC short kit will allow you to load 2½-inch shells, and Ballistic Products has the reloading materials you need.