FOR THE SAKE of the story, I’d love to tell you I had a long-term relationship with the biggest mule deer of my life, that I had watched him for days and discreetly patterned his distinctive behavior. Or that I had tracked him for hard miles across the deep desert of northern Sonora, Mexico.

The truth is that I had seen him for only about 30 seconds before I shot, the steady stream of trucks on Mexico’s Federal Highway 15 droning in the middle distance and my crosshairs bouncing as I awkwardly balanced my rifle on the angle-iron rail of my mobile deer stand mounted to the bed of a pickup. I would have shot sooner, but I could see only one antler and not quite half his body through a window in the brush at 180 yards, and while my companions shared their speculations in hushed and rushed Spanish about whether he was el grande or something less, I pictured where I’d place my bullet when I finally got the go-ahead.

The deeper truth: I missed that shot, sending 175 grains of Berger boattail toward the Sea of Cortez.

Maybe it was what happened next—dutifully walking to the spot where he stood, sighting back to the pickup through shirt-catching branches of mesquite and paloverde, searching the rank grass and cactus in vain for blood—that contributed to my ultimate success and makes this a story worth telling.

Everything up until this empty moment had been a gift. The fact that I was here at all, a guest of outfitter MX Hunting in the deep desert north of Hermosillo, was a gift from my friend Nick, who had booked this hunt before work conflicts gummed up his availability. The appearance of the buck itself was a gift from the mule deer deities, who must have considered the years, meetings, and money I’ve invested in their habitat and welfare as a national board member of the Mule Deer Foundation. The dimensions of the one antler I could see before my resounding miss, a wide left side with what looked like an extra tine sprouting from a heavy main beam, was a gift of this uninterrupted chaparral that allowed the buck to grow old and pack on inches of bone by staying scarce.

But on my walk back to the pickup, carrying the weight of failure and sensing the rough edge of silent judgment from my hunting companions, these gifts all felt as heavy as lead.

I climbed back into the high rack, an 8×8-foot metal cage welded to a steel scaffold that was itself ratchet-strapped into the bed of a full-size pickup. Kobe Carlson, my guide and interpreter, used it as a verb.

“Looks like we’ll be high-racking,” Kobe had told me when he picked me up at Hermosillo’s airport a few days earlier. “It’s about the only way to see deer when you’re down on the desert floor.”

This wasn’t how I anticipated hunting Sonora’s outsized mule deer. I expected we’d climb one of the ancient volcanoes that sprout from the desert floor every 20 miles or so and glass with powerful optics until we spotted a buck worth our pursuit. Or I expected we’d cut a big track and follow it until we found its owner in some scorpion-infested arroyo. I pictured making an offhand neck shot at a wide-racked buck as he turned to check his backtrail.

I certainly didn’t expect to be this close to civilization. At the truck stop where we turned off Highway 15, the Mexican equivalent of an interstate highway and the main conduit for northbound melons, tomatoes, and corn, a blind woman hawked bags of pecans and a man in filthy clothes cleaned windshields in hopes of a tip.

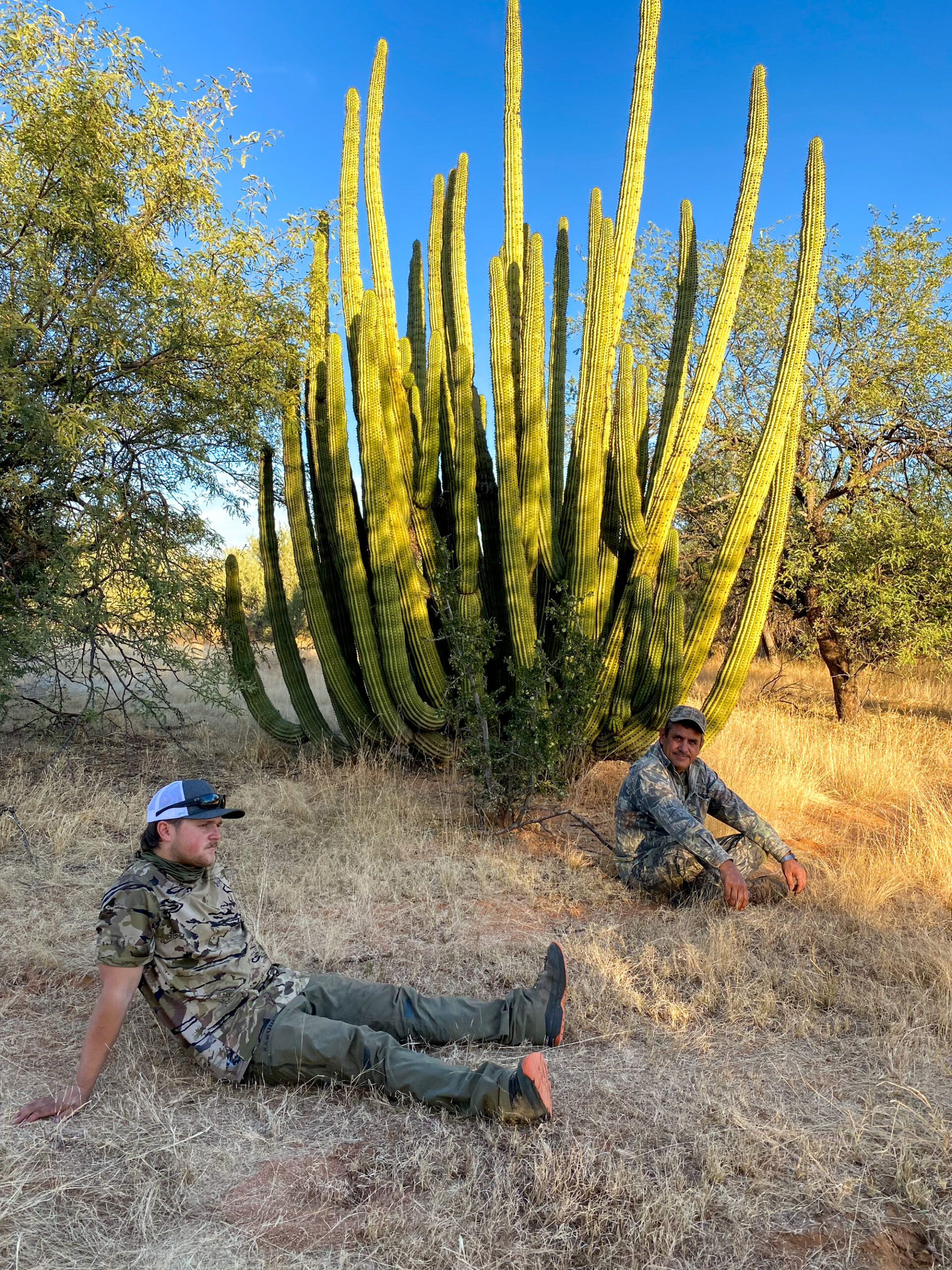

I didn’t expect the desert to be this lush, so full of tall and short and middle-sized plants, the pitaya cactus soaring to the azure sky, the palo fiero—or fire stick—competing with mesquite to make every path and dry waterway impenetrable. So much grass and knee-high cholla, called “jumping cactus” for its irritating habit of clinging to your clothes even when you don’t brush its antlered branches.

Neither did I expect to be hunting with an entourage. Opposite Kobe in a corner of the high rack, Hector German Arce sat stoically. In his hand he held a radio that he used to communicate in Spanish with our driver, a swarthy Sonoran named Luís. When we wanted a closer look at something, Hector radioed Luís, who stopped the truck, sometimes backing up to get a better look at what appeared to be a deer’s ear in the brush, or maybe the glint of an antler.

Among the terms I heard Kobe and Hector trade throughout the day: el camino. The road. Any buck I’d have a hope of killing would have to have poor judgment to loiter in view of the rough ranch roads that we crept along, flushing quail and sounders of startled javelina, and sometimes stopping to lop mesquite branches with pruning shears Hector kept by his side.

This was our second day of high-racking, what can only be called trolling for deer. Today, we’re joined by Martin, the owner of this cattle ranch that appeared to have way more Gambel’s quail, javelina, and coyotes than cows. Before sunup, the desert all purple and flannel gray as the sky lightened above the Sierra Madre mountains in the east, we pick up Martin at his roadside hacienda. A couple of eager dogs follow the pickup as we pull away from the house, the high rack swaying and creaking on the corrugated ranch road. I can’t tell if Martin is coming along because he’s suspicious of us or just curious about how this rifle-toting gringo might tag a deer in cover better suited for a shotgun.

I had the same question. During yesterday’s troll through this same tight brush, I cussed my choice of gun. I was shooting a new Browning X-Bolt chambered in 28 Nosler and topped with a Huskemaw scope, a combination designed for engaging small targets beyond 600 yards. Here, I couldn’t imagine even seeing a deer outside of 50 yards through the screen of brush and thorns. This is country and a style of hunting better suited for buckshot, or at most a semiauto .308, like the boar hunters in Europe use to take driven game that’s ducking through cover at double-speed. I realize I’ve shown up to a knife fight with a surface-to-air missile. But I turn my scope down to its lowest magnification, set the parallax at 50 yards, and when we flush a covey of quail or stop to open a gate, I practice swinging through moving targets both real and imagined.

Yesterday, we had a single antlered target to consider. In late morning, we busted a small group of does and fawns. Around the next corner a buck stood frozen in the brush. Hector radioed Luis, who stopped and eased the truck backward until Hector halted him. Somehow, the buck stood his ground, still as a statue, and we sized him up with our optics. Kobe figured him a mid-180-class buck, but we couldn’t see all of his wide rack. Just as we were about to inch backward, the buck busted and as he juked through the mesquite he showed us the goods. He was a handsome 4×4, no eye guards but deeply forked tines, beams shining like polished walnut.

I could tell by their staccato Spanish, and the frequent use of the term burro, by which they meant mule deer, that both Kobe and Hector second-guessed their hesitancy. It’s early December, a full month before the rut, with abnormally heavy cover thanks to a late monsoon season. We might not see a better buck.

The Pull of Sonora

This is precisely what Justin Richins wants me to know. A longtime Utah big-game outfitter who started MX Hunting a decade ago, Richins says hunters—I can tell he means me—who show up in Sonora expecting to see a 200-inch mule deer behind every saguaro need to understand the calculus of Mexican hunting.

Yes, he says, the desert is capable of producing outsized bucks. But just as with old bucks everywhere, their numbers are low. When you consider the overall low densities of deer here, the impenetrable brush, plus the relatively small hunting properties, encountering a mature buck is a gift, not an expectation.

“The reality is that if you come here long enough, you should be able to kill a 205-inch buck, but it can take years,” says Richins, who makes his point by enumerating clients who come for three, five, even 10 seasons before they tag a buck that breaks the magical 200-inch benchmark.

They keep coming because Sonora produces the largest mule deer on the continent. Partly it’s genes that allow it to grow wide racks with deep forks. But the main ingredients are situational.

“For experienced mule deer hunters, the chance to hunt an age class of bucks that we see only occasionally in the States is probably the biggest draw,” says Richins. “If you think about the core mule deer range in the Rockies, it’s almost impossible to consistently hunt deer over 4 1/2 or 5 years old because of winterkill. That’s just not a factor in Sonora. Down here, even during bad droughts, we might see a little decrease in antler size or deer congregating around water sources, which can lead to predation and disease, but it’s nothing compared to the widespread winter mortality we see in Utah or Wyoming after a bad drought year.”

Richins says the added stress that shed hunters and recreationists put on winter-range deer in the States is nonexistent in Sonora. So, too, is human harvest, because so few Mexicans own firearms.

“Bucks may move during the rut, but they’re primarily residential deer,” says Richins. “Down here we don’t have all the additive loss from migrating deer getting hit on roads or caught in fences. There’s no competition from elk or whitetails. Plus, the desert vegetation is surprisingly high in protein and nutrition, so bucks put on inches of antler at a pretty fast pace. Deer can roam pretty much at will on those big, vast desert floors, so they’re not getting targeted on a single property. And there’s not much predation. Mexican coyotes are maybe half the size of American coyotes and really aren’t a factor.”

The antlers of Sonoran burros are as unlike Utah’s heavy mountain bucks as Saskatchewan whitetails are from Georgia’s pine-country deer. Wide, symmetrical, with long tines and deep forks, Sonoran mule deer score so high mainly because they have so few deductions. These are the platonic ideal of typical mule deer, and most mature 4×4 desert bucks with at least 30-inch spreads score right around 200 inches.

Add up all those perspectives, and it’s no wonder that serious mule deer hunters shell out five figures for the chance to hunt Sonora’s bucks.

The Gringo and the Don

Less clear to me is whether Kobe or Hector is my guide. Kobe seems to take control of each situation, but he’s deferential to Hector when it comes to hunting. It would be hard to pick two more dissimilar rackmates, both trying in their own styles to find me a muy grande buck.

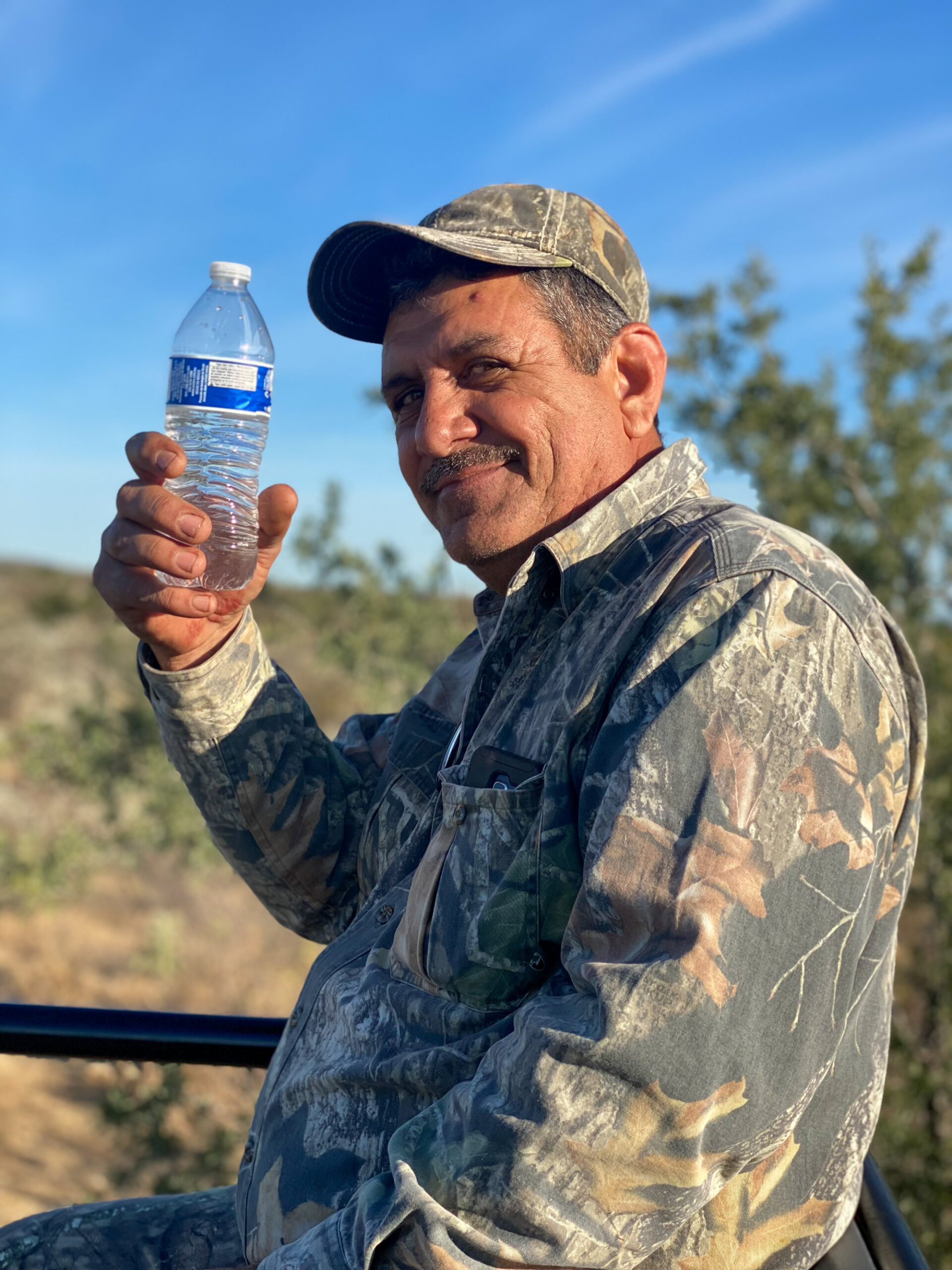

Kobe, at age 22 and working on his first mustache, dressed entirely in Kuiu camouflage and packing energy drinks, is the very picture of the Westie, the overeager Western hunter turned internet meme. He’s impatient and restless as we log empty miles atop the high rack. The laconic Hector, on the other hand, a clipped mustache framing his craggy face, is central casting’s idea of an Old Mexico hunting guide. Hector’s patience with his fellow guides and the gringo hunters has earned him an honorific title around camp.

“Don Hector,” the cooks and guides all call him, deferring to his seniority and experience.

If Hector personifies the landscape of Sonora—inscrutable, prickly, generous, and kind—Kobe is familiar to trophy-seeking deer hunters.

A Utah kid who learned Spanish during his Mormon mission to Argentina, Kobe returned with a wider view of the world and a particularly useful skill for a kid who loves to hunt: fluent Spanish. Richins hired him to help with Sonoran hunts, partly for his language skills, partly because, by his own admission, he’s really good at scratching deer out of tight cover.

I’ll get some of Hector’s biography wrong, or at least half right, owing to our hamstrung conversations crippled by my laughable Spanish and his slightly less laughable English. But I’m not apologizing, as misunderstanding is the basis of most mythology. If Don Hector isn’t quite mythic, he’s at least that authentic archetype you hope to encounter when visiting a storied destination.

Hector was born into Old Mexico’s hunting culture. Back in the 1960s, his mother worked as a housekeeper at an old downtown Hermosillo hotel, the kind where you can find gracious accommodations and authentic Sonoran food, plus whatever local recreation you might be seeking. Owned by one of Sonora’s first international hunting outfitters, the hotel lodged American and European hunters, and young Hector was a constant and reliable presence there. He would be asked to run errands for the gringos, then, as a precocious 10-year-old, to drive them around town and out to the ranchos where the hunting for mule deer and Coues deer and even desert sheep took place. Soon Hector found himself out in the country full-time, helping spot game with his excellent eyesight and indefatigable work ethic. That apprenticeship eventually matured into regular guiding gigs. Late in my week with him, our fellowship relying as much on images as words, Hector showed me pictures of himself posing with record-class desert bighorns, 210-inch Sonoran mule deer, and Coues deer that would place high in the record books.

In many of the photos, Hector posed with his own head tucked between the antlers or horns of the dead animals, his brow to their brow. I didn’t have the right words in either language to ask him about that particular behavior.

These days, Hector runs a sporting goods store in the front room of his Hermosillo home. He makes knives and smiths guns and works as a seasonal guide for MX Hunting and other outfits all around Sonora.

Now, our second day trolling this desert-floor ranch, we have the addition of the landowner, Martin, to help us pick out these cryptic Sonoran bucks.

The Gift

Soon after collecting Martin, we stop along a gas pipeline that cuts through the ranch to assess a young burro. The buck turns himself inside out to dissolve into the mesquite, and while the rest of the high-rack crew watch him disappear, I look down the pipeline cut that parallels the interstate and provides a rare alley of visibility through the desert jungle.

The second deer is more than halfway across the cut when I spot it, his head obscured and moving quickly toward the interior of the ranch, but I’ve seen enough mature mule deer to know that its square back belongs to an older buck. The buck is standing broadside and watching us at 180 yards just inside the pipeline cut as I get the attention of my entourage. This is when the chatter about whether he is worth shooting or not starts in earnest, and when I get him in the crosshairs of my wobbling riflescope, and when I miss.

Back on our trolling pattern, as the Mexicans chatter about some a topic I can’t comprehend, the sun melts shadows and reveals a landscape empty except for last night’s tracks and a scattering covey of spastic quail. Luís turns a corner and follows a perimeter fence, my rackmates already talking about lunch.

I see the buck ahead at maybe 60 yards, somehow showing no indication that he spots our truck. All I know is that he is antlered and moving with muscular purpose as his square back sails over the fence and onto the road in front of us. The truck is still rolling when I take an offhand shot that feels right, but somehow the buck doesn’t crumple. Instead, he melts into a ragged garden of rama blanca, the low-slung white-leafed shrub that defines much of this part of Sonora. The second shot must confirm to him that he is being hunted, because the buck turns on his afterburners, and when he clears a mesquite stand, I throw another round his way, but I can tell immediately that I pulled my head, sending the shot high.

I am distantly aware that no one in the high rack had assessed the buck, or given me the okay to take the shot, or even knew what was happening as the truck lurched to a stop. But I’m tunneled into my scope, and when the buck bounds into his next stride, I’m on him, pulling through the shot like I would with a rocketing rooster back home.

The trigger break feels good, but the recoil throws me out of the scope, and besides, I’m out of shells. I fumble a loose round into the chamber, slam the bolt home, and draw down on the desert, waiting for a last wild shot at the parting buck. But the rama blanca and the cholla cactus are still. I am aware that I can’t even hear the interstate. The only sound is the hollow clink of empty cases rolling metallically on the deck of the high rack, now shrouded in almost comic silence.

Slowly, in a deliberate procession, the lot of us descend the high-rack’s ladder and step into the chaparral. I push two more shells into the magazine and head to the spot of my last shot while Martin and Kobe wade into a stand of hip-high brush. I am bracing against another bloodless inspection when Martin gives a “Hooray!” which sounds in Spanish just as it does in English. I claw my way through thorns and find him standing over a grotesque amount of fresh blood. Together we push ahead and find the buck piled up in the brush maybe 30 yards beyond the blood.

Of all the images I’ll remember from this moment, none is as simply joyful as Martin, his chemically-white teeth gleaming beneath his American-flag hat, giving me two thumbs up before enveloping me in a hug. I can’t recall the last time an American rancher so gleefully celebrated a hunter’s kill.

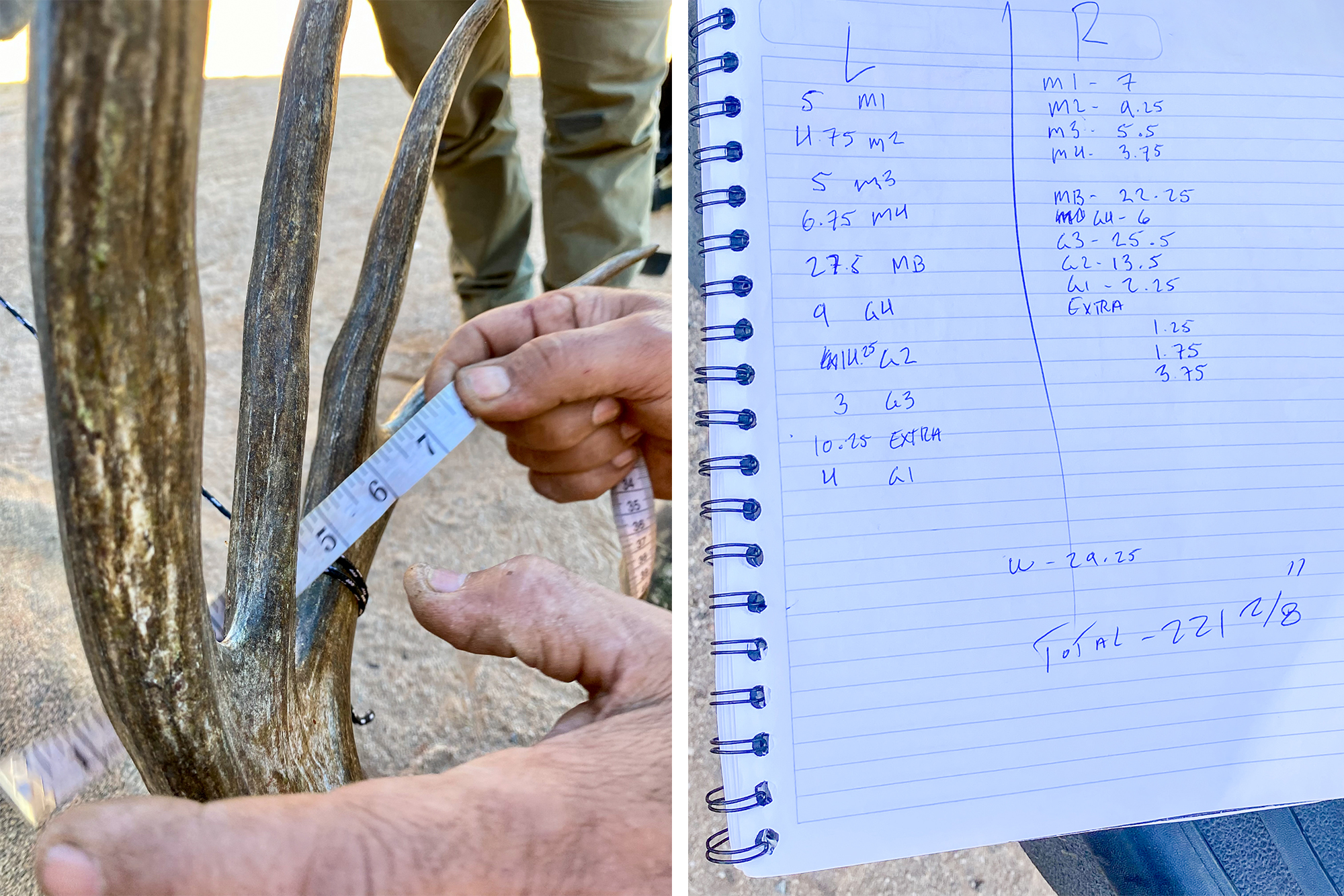

The other indelible image: the buck’s astonishing rack, so wide that his head seemed to levitate above the earth, and more points and beam than I thought possible. Then Kobe steps into the clearing, looks down, and says simply, “Holy shit.”

Muy Grande

The next memory is Don Hector, smiling at me as though we share a secret. He walks up to the nose of the buck, takes its antlers in his hands, and assesses the headgear. Then he puts his own head on the brow of the buck, as though the buck’s antlers were his own backward-growing rack. I later learned this is Hector’s gesture of respect to the buck, but in the moment, it’s laughable, and breaks whatever tension lingered from the unbidden hail of gunfire.

The remaining tension dissolves when Hector walks over to me, puts his hands on my shoulders, and laughs. “Speedy Gonzales!” he proclaims, and then pantomimes the act of me racking the rifle’s bolt in double-time while swinging on the running buck.

I realize that my action upon seeing the burro, which we learned had followed a well-used game trail down from the gas pipeline to the fence where we intercepted him, was really simple reaction.

It was an unthinking moment that converted gift to possession, the seconds between seeing the buck and putting my hands on him. But, unlike charity, it was earned through a lifetime of hunting, of recognizing the incalculable moment between the improbable and the possible. It didn’t hurt that I had spent the months leading up to this moment with a shotgun in hand, walking up wild-flushing pheasants and grouse in my native Montana.

I didn’t recall seeing the running buck in my scope, or even the stepped-down reticle inside the optic, only shouldering the rifle and pushing the barrel through my target. Had I waited, or turned to my companions for permission, that buck would have been swallowed by the desert, probably never to be seen again by me.

But now, seeing the dead buck clearly for the first time, I am overwhelmed with the benevolence he represents.

His right side, the side I couldn’t see when I made that first errant shot, has an extra main beam. As I surmised, his left side sports a bonus in-line point, plus a pair of stickers on the underside of the beam. His right bases look like those of a raghorn bull elk, wide, encrusted with erupting dimpled points, the entire surface textured in an emerald patina from rubbing palo verde branches. He might be non-typical as all hell, but he also shatters the 200-inch mark with measurements to spare.

Somehow more significantly, I notice a long red mark on his brisket, almost like he had been burned by a curling iron. It was the hot trace of a grazing bullet, probably my second shot just as he jumped the fence in front of our pickup.

I hold his wide antlers and suddenly break out in chest-heaving laughter that edges toward hysterical sobbing. The entire ordeal, from seeing the buck cross the pipeline cut to scoring on my last desperate shot, had spanned less than 10 minutes. But this moment, in a tight clearing in the Sonoran Desert, holding the incredible buck and basking in the redemptive glow of admiring companions, is the greatest offering a mule deer hunter could ask for in a lifetime of seasons.

As we together drag the buck through the pants-piercing cholla cactus and out to el camino for pictures, Don Hector turns to me, holds my gaze for a single second, and throws me a wink.

Read more OL+ stories.