Whitetail hunting in America has boomed and busted. After years of record highs, harvests in many of the powerhouse deer states are down, and they’re staying down. The top deer experts around the country are accepting this as the new normal. So what have we learned? Let’s start with these six rules.

1. Expectations are Too High

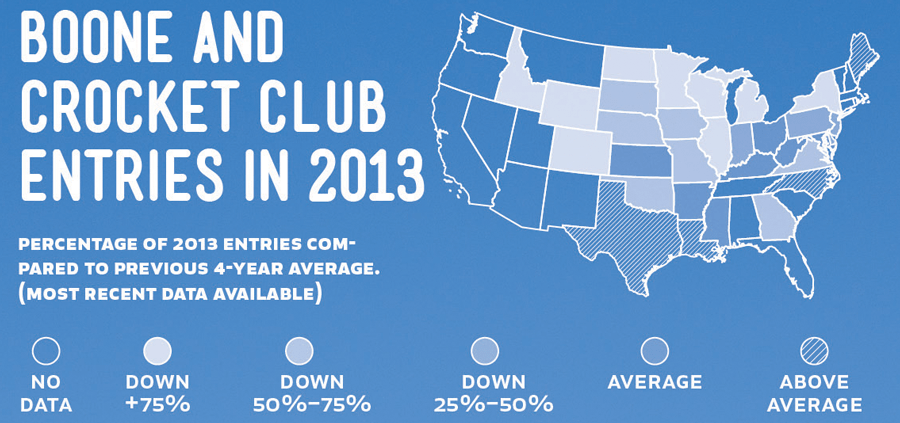

The average deer hunter in America has higher expectations today than ever before. Flip the television to any hunting show and you’ll find a host like Mark Drury of Drury Outdoors, who killed six bucks last season scoring more than 130 inches, four of which were over 150. Or pull up your Facebook newsfeed on a random day in early November, and you’ll probably see 10 buddies showing off pictures of their giant bucks. But just because trophy deer are more present in the media doesn’t mean that they’re easier to kill. In fact, Boone and Crockett Club entries are down across the country (see map at right).

Average deer hunters have expectations that cannot be met and they’re left disappointed, says Neil Dougherty, an experienced wildlife consultant who works on whitetail properties across the country. “So many people I speak to today are living in Outdoor Channel la-la land, where every deer has to be four years old and 150 inches or they won’t shoot it. And these guys only have a property of 200 acres or less,” he says.

Back to Reality

So where should you set your expectations? Dougherty says to start by determining your goals. Are you most interested in antler size, age class, numbers of deer, or just an overall quality hunting experience? Lastly, what are you willing to give up? Are you really willing to eat your buck tag?

Once you decide on a set of criteria, you need to research the standards for that criteria in your hunting area. If you’re interested in antler size, look into local big-buck club data, or B&C and Pope and Young Club record books for your county and focus on the last 10 years. If you’re looking to manage for age, local wildlife biologists might be able to provide insight into what age class of deer is typically being taken in the area. From there, Dougherty says, set your expectations based on the habitat you’re hunting.

“The top 10 percent [in age class or antler size] for that area is what a landowner should realistically strive for, but that’s only if the habitat is really tuned up,” he says. If you don’t have high-quality cover and food, targeting the top 25 percent in age or antler class is a more realistic goal. But if the fun starts to wane, get back to the basics.

“Sometimes you just need to be successful,” Dougherty says. “Maybe you take a buck you normally wouldn’t—maybe it’s a younger age class. But if things all come together—you’ve worked really hard and an opportunity arises and you’re excited—you should be able to kill that buck and do it unapologetically.” —Mark Kenyon

2. Every Deer Hunter is a Manager

I will always remember the summer of 2012. It was the summer that smelled of death.

Southerly breezes would carry the stench of rotting whitetail carcasses—deer that had died from the worst outbreak of epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) in Michigan history—from the nearby river bottom toward my house.

One year later, I bought a small chunk of hunting land that adjoins that river bottom. It might seem like a stretch to talk about “managing” deer that live on 17 acres, but it’s my responsibility to do the best I can. And every decision I’ve made links back to that summer.

It wasn’t that I mistrusted the antlerless quotas set by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. It was that I simply understood a harvest quota covering a county-size unit should not be a one-size-fits-all guideline, and I had positive, putrid proof that EHD had taken a sizable number of deer in my area. Even after the local EHD die-off, the state was offering antlerless tags in my unit. I could have taken five does that year, but I didn’t, knowing that any additional doe mortality would have been devastating.

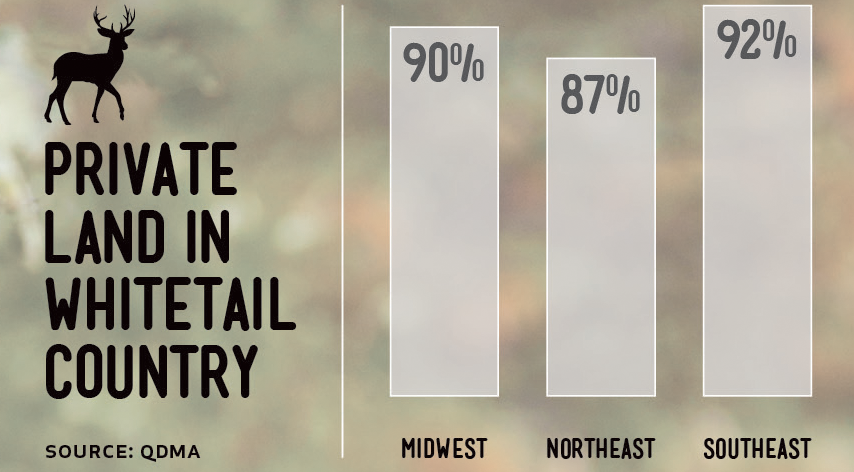

Dr. Russ Mason, wildlife division chief for the Michigan DNR, tends to agree. “We can do whatever we want, as a state, to manage the 20 percent of Michigan that we own. But landowners and hunters will ultimately determine the management direction on the 80 percent that we do not own,” he says.

So Michigan is developing a land co-op coordinator position and has created programs specifically to focus on private land management. And they are not just focusing on basic methods of management like antler-point restrictions. They’re looking at complex issues of habitat quality, density goals, and landowner collaboration.

“There is this notion that ‘I’m willing to do the right things but my neighbor isn’t.'” Mason says. “So we talk to that neighbor. And guess what he says? ‘I’m willing to do the right things but my neighbor isn’t.’ As hunters, we’ve got to do better than that.”—Tony Hansen

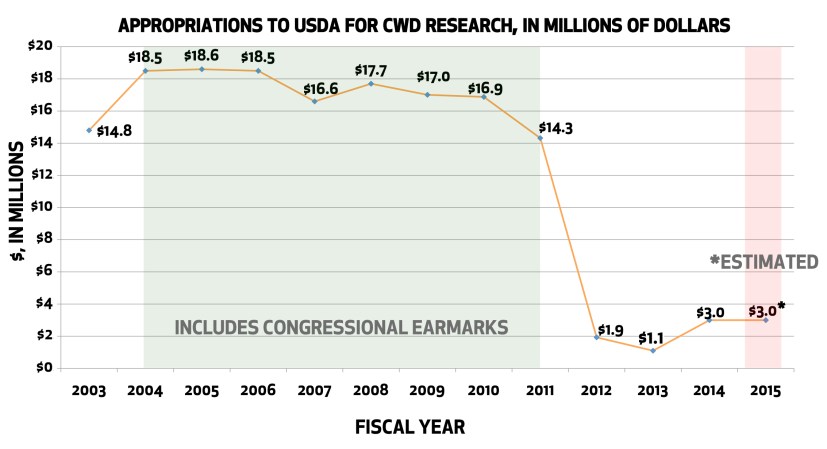

3. CWD Is Still the Greatest Threat to Whitetails

Management, by definition, implies a system of processes intentionally designed and implemented to achieve a set of desired results.

Want to improve the age structure of bucks in your area? Protect young bucks and, over time, the percentage of mature animals should increase.

But there is an aspect of deer management that is beyond control, an aspect that has had measurable affects in many areas of whitetail country and will likely continue to have an affect long into the future: disease.

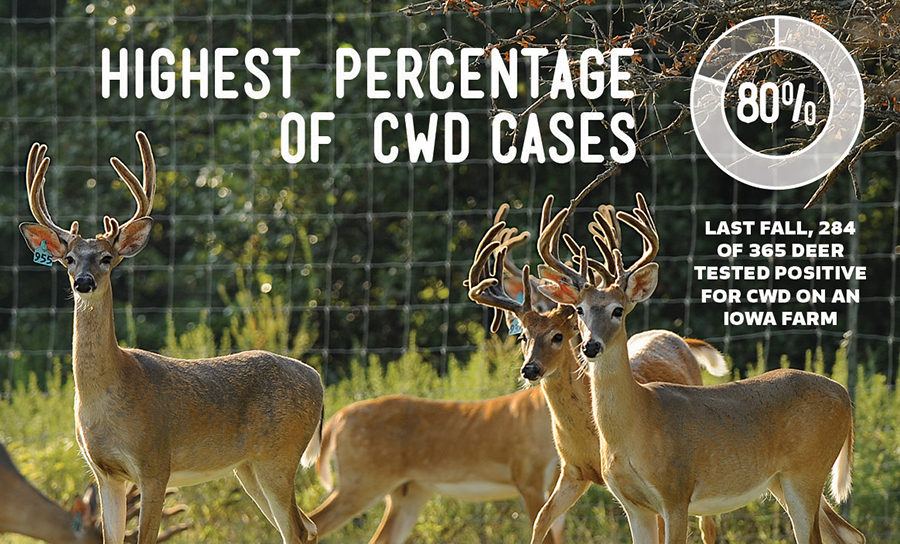

Epizootic hemorrhagic disease (EHD) has stolen headlines in recent years with massive deer kills in storied deer-hunting locations like Montana’s Milk River and western Illinois. But the deer experts I spoke to insist that chronic wasting disease (CWD) is still the greatest threat to deer, both locally and nationally.

CWD is an always fatal, contagious neurological disease. It is transmitted by infected prions from infected animals. It’s unknown just how long these prions can last in the soil and environment, but it has proven to be resistant to extreme heat and disinfecting procedures.

“CWD is the disease that I have nightmares about,” says whitetail expert Grant Woods. “In areas with CWD, no one can predict what will happen because we do not know. Once it’s there, it’s likely there forever. It seems like hunters in areas with CWD have learned to live with it. But we need to get it back on the front page. We are talking about a national treasure when talking about our whitetail population. And CWD is a very real risk to that treasure.”

To Woods and Dr. Russ Mason, wildlife division chief for the Michigan DNR, future management decisions involving CWD should focus on stopping its spread, not controlling the areas where it’s been found.

“CWD is more of a biological poison than a disease. I would compare it more to radioactive waste than something like the flu,” Mason says. “The experience in Wisconsin has shown that we can’t just kill all the deer in the area and stop it. They’ve done that and the prevalence rates are higher than they’ve ever been. The only success we have seen are in areas where the very first animals to be infected were found immediately and killed.”

To Woods, the first, most critical step in stopping the spread of CWD is obvious: Stop the transport of captive deer.

“The data shows very clearly that most instances of CWD infection has a captive cervid component—the infection occurs near a captive cervid facility,” Woods says. “And it’s not mom-and-pop operations but large, aggressive farms that are shipping deer. When we ship deer, bad things happen.” —T.H.

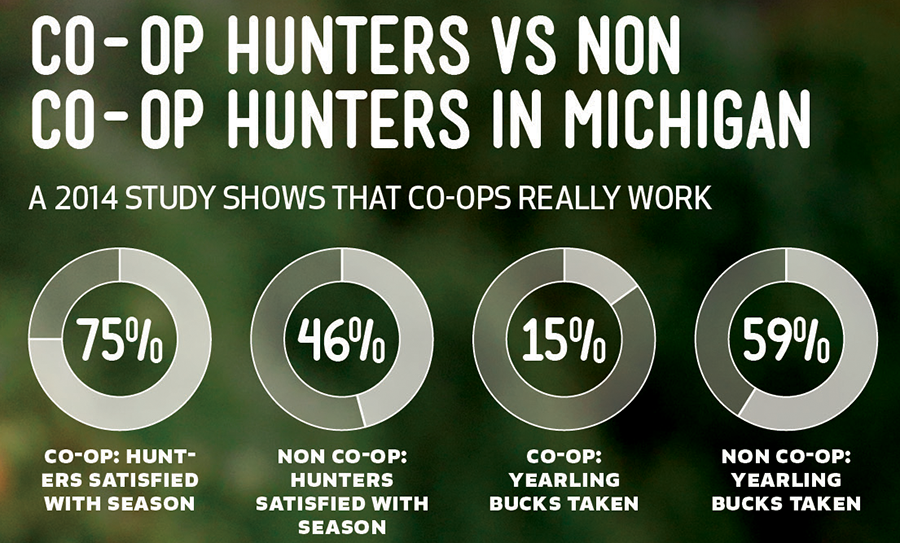

4. Co-Ops are the Future

Land co-ops might be the next cornerstone of state-level management, but they’re also the most consistent way for an individual hunter to kill mature deer. This is so for two simple reasons: (1) In order to effectively manage deer, you need to have access to the majority of the deer’s home range. (2) Most individual hunters can’t afford to buy or lease that much property. A quick example: A buck’s home range can span a square mile or more, and on average, a Quality Deer Management Association member owns fewer than 200 acres of land.

Nobody knows this better than renowned whitetail photographer Charlie Alsheimer. In 1989, Alsheimer hunted with Al Brothers—who many consider to be the grandfather of quality deer management—in Texas and was blown away by the program there. Brothers persuaded Alsheimer to start a co-op where he lived and hunted in western New York, which was the heart of if-it’s-brown-it’s-down deer-hunting culture.

Alsheimer went to neighbors and told them what he planned to do. So, a group of four neighbors made a gentleman’s agreement to manage their combined 750 acres.

Their rules are simple and attainable: Target 3½-year-old bucks and older. Each hunter can kill only one buck per season. First-time hunters can kill any legal deer. Everybody participates in the doe harvest.

By the fourth year, Alsheimer had killed a 140-inch 9-pointer and his neighbor had shot a 150-inch 10-point—both were their biggest New York deer ever. Alsheimer and his buddies don’t kill trophy bucks every season, but they’ve had two decades of good hunting for mature deer.

Quality deer management co-ops are by no means a new concept, but groups like Whitetail Properties and the QDMA are now having more success implementing them. Whitetail Properties agents have taken to setting up “neighborhoods,” stretches of adjoining properties that are all managed by like-minded hunters. “Deer hunters are a lot more educated today than they used to be,” says Whitetail Properties land specialist Aaron Milliken, who sells land and sets up management neighborhoods in western Illinois. “And by now, quality deer management is proven. We’ve got the numbers to back it up, so it’s not as hard convincing people.”

Both Milliken and Alsheimer agree that patience is the key to starting a co-op. Over beers (or coffee), tell neighbors what you would like to do, and if they like it, great. If not, don’t pressure them. Sometimes a holdout will decide to join after he sees the co-op’s success and some trail-camera pictures of trophy deer.—Alex Robinson

5. It’s Political Science

Photo by Charles Alsheimer

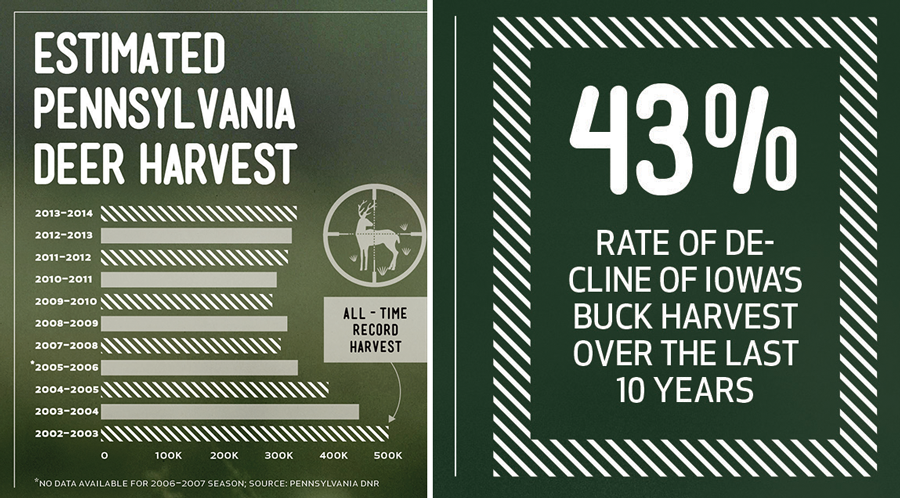

Deer management, like other political issues, isn’t always guided by pure science. Often it’s the constituents who complain the loudest that end up calling the shots. You can see such a struggle being played out in Pennsylvania. In the 34 years that Matt Hough has worked for the Pennsylvania Game Commission, he’s responded to ever-changing public opinion.

“You set antlerless harvests to get the population down until hunters start clamoring that there aren’t enough deer, so you back off and the pendulum swings the other way,” says Hough, who is now executive director of the game commission. “Eventually the farmers and foresters complain about too many deer, so you jack up the antlerless harvest and swing the pendulum back.”

As a way to balance the varying public demands, the game commission adopted an ecosystem-based management plan in the early 2000s. The concept was to manage the deer herd based on the habitat—not deer harvest numbers—to promote a healthier herd and a more diverse state forest. (The state’s timber industry has a total economic impact of $27 billion annually.)

Enter Gary Alt’s stump-speech campaign: antler-point restrictions and massive deer harvests. Now, 15 years later, some deer hunters are happy with the results, which tend to be fewer deer sightings but more mature bucks. However, many others are ready for a coup. A 2011 game commission survey found that only 27 percent of hunters were satisfied with the number of antlered deer they’d seen.

Last summer, a coalition of sportsmen’s groups got five of their own deer-hunting bills drafted by state representatives. Their tactic was to sidestep the commission and run the bills through the legislature (a worst-case scenario for the commission). The bills weren’t voted on, but the message was heard loud and clear by the board of commissioners.

“I think that the majority of commissioners feel they need to increase the herd. [In 2000] they reduced the herd, and they stayed the course. But I don’t think they can keep it up.” Hough says. “The commissioners get pounded.”

There’s still opportunity for Pennsylvania deer hunters and hunters across the country who find themselves in a similar scenario. The new hunting environment in the state favors more dedicated deer hunters, Hough says. There are longer seasons and more tags available now than ever before. So although there might be fewer deer killed, the most die-hard hunters have a chance to punch their tags during the bow or late muzzleloader seasons.

“Times have changed,” he says. “The most successful hunters adapt.” —A.R.

6. You Can Shoot Too Many Does

For the better part of the last two decades, the mantra for many serious deer hunters was to waylay does. Deer densities were too high and the focus had shifted from seeing a lot of deer to targeting mature bucks. If a hunter decided to pass on young bucks, shooting does was a good way to put venison in the freezer. More recently, though, hunters have learned that you most certainly can shoot too many does, and when you do, the consequences are severe.

Take, for example, the scenario that Glenn Horton, former president of the Cherokee Preserve Club in New York State, experienced in the early 2000s. A typical hunting season at the club would see the members take 8 to 12 bucks a year. But then the state offered a significantly higher number of DMAP antlerless tags. The club was offered an additional 25 antlerless tags, and Horton says that during the first year, members used almost all of them. Then a bad winter hit the Northeast. After a second year of a high doe kill, the club, which has more than 35 members, killed only three bucks.

“We definitely put a hurt on the population,” Horton says. “That year changed everything.”

The club suffered years of poor hunting before deer numbers bounced back.

This isn’t just an isolated case, either. Neil Dougherty has seen it happen on some of the properties he manages. With more severe mortality factors affecting deer today (EHD, predation, hard winters), wildlife managers are learning that deer populations, in many cases, can’t handle high hunter harvests.

“When we have all this stuff together,” Dougherty says, “we need to be extremely sensitive to an overharvest of does.”

Hunters can’t control winter severity or EHD outbreaks, but by being careful not to mismanage does, we can at least avoid total disaster. This should be done through monitoring doe and fawn numbers in the spring and summer with consistent trail-camera work.

According to Dr. Russ Mason, wildlife division chief for the Michigan DNR, maintaining higher numbers of does will likely position the herd for a faster recovery from an EHD outbreak or mass winter kill. The key is to not put the herd in a position where it can’t bounce back. _—M.K. _

Correction: This article originally quoted Grant Woods as stating that every instance of CWD infection has a captive cervid component.