As I clicked “submit” on the license application, a sense of melancholy came over me—which was surprising considering I was certain to draw the Utah trophy bull elk tag. My thoughts drifted back nearly two decades to the first time I applied for it.

Optimism comes easy in one’s youth, and I was sure at the time that I’d get lucky and draw early. My “unsuccessful” notifications were met with surprise and strong disappointment those first few years. After that, I felt bitterness and betrayal at the rejections. I lived in the hunting unit, after all. Shouldn’t I be given the opportunity to hunt in my own backyard? By year 9 or 10, I had matured and become resigned to the idea that luck wasn’t on my side. I’d just have to keep applying until my name reached the top of the list.

Seventeen years after I submitted my first application, I finally had enough preference points to draw a muzzleloader tag. But if I waited another four or five years, I could probably draw a rifle tag instead. I agonized over the decision before coming to a realization: Despite a powerful desire to harvest a truly remarkable bull, what I really wanted was a great experience. And what would make the hunt most meaningful and memorable for me would be to hunt with a traditional weapon. The choice was easy: it would be a flintlock longrifle.

TRADITIONAL ROOTS

I spent my youth dragging around a traditional bow or muzzleloader of one kind or another, competing at local events, hunting, and just enjoying the company of such beautiful weapons. When modern inline muzzleloaders arrived on the scene, I felt no kinship with them. Traditional longrifles have an extensive and often noble history of conquest, adventure, and defense of country. They have beauty and soul, and I couldn’t find any of that in the new generation of muzzleloaders.

For my elk hunt, I chose to use a rifle built by my friend Steve Baxter of Tennessee. It’s a flintlock of 1790s-era design, sporting a 42-inch octagon-to-round .54-caliber barrel. Hand-cast 230-grain lead balls smoked downrange at 2,050 feet per second, grouping just under 2 inches at 100 yards. The rifle was ready, but first I had some other business to attend to.

“When inline muzzle-loaders arrived, I felt no kinship with them.”

In addition to my elk tag, I’d drawn a Utah general season archery buck tag. Some great mule deer lurk along the edges of the high desert timber near my home, and for the first time in several years I’d have some time to hunt them.

I opted to use my favorite longbow, a Fox Archery Royal Crown deflex/reflex bow that won a blue ribbon at the Professional Bowhunters Society’s 2006 banquet. I was lucky enough to win the bow at auction that night, and I’ve had some incredible hunts with it over the years. I have a lot of confidence in the bow—it, too, has soul. And with the string pulling 60 pounds at 29.5 inches and pushing a 610-grain arrow, it hits very hard.

SECOND CHANCE BUCK

Two weeks into the archery hunt in southern Utah, I still hadn’t killed a buck. Somehow the big ones I was hunting had patterned me better than I had them. I took a couple of days to sit back, observing the deer from a distance. I realized that I needed to move my setup deeper into the timber, closer to the bucks’ bedding area. I tracked them to the top of a mountain and hung a stand 10 feet up a tree that had buck tracks on either side. The tree was puny, though, and any quick movement while I was on stand caused it to sway. I would have to draw my bow very deliberately.

After letting the area settle down for a day, it was time to hunt. I hiked the mile and a half from my truck to the stand in 85-degree heat. Stuffing my sweaty clothing into my pack, I donned a thin, scent-free base layer and climbed my little tree. With the wind in my face, several yearling bucks passed within easy range, but I knew of at least three superb bucks in the area and was determined to hold out for one.

A short time later, I heard more deer heading my way—a lot of deer. One of the three monster bucks was among them, and he stopped broadside at 14 yards. I began to draw but had to freeze to avoid getting busted by two other bucks. The monster sauntered under my tree and stopped again to nibble on a little cedar bush. He was 4 yards from me, his vitals obscured by the lower limbs of my tree. If I’d had a heart condition, it would have claimed me right then and there. Several more bucks passed by, and soon this big fellow decided it was time to go. As he walked away I drew my bow, trying desperately to get off a good shot. I had to reverse cant my longbow to get on the deer, and just as I was about to drop the string, my arrow fell off the shelf. In an instant he was gone, and I stood there in shock. How does one spend several minutes just 4 yards from an unaware buck without putting an arrow in him? I’m still not sure of the answer to that question.

“How does one spend several minutes just 4 yards from an unaware buck

without putting an arrow in him?”

Dusk was falling and my light soon would fade. I was still in slack-jawed disbelief when I heard another deer approaching quickly. As he passed 12 yards from my tree, I drew my longbow. He saw movement and stopped, staring in surprise at the funny-looking lump up in the tree. I dropped the string and watched in awe as my arrow vanished exactly into the spot on his torso where I was looking. In a matter of minutes, I had gone from deflation to elation. I’d just killed one of the three monarchs of the region, and my biggest archery buck ever.

ON TO THE BULLS

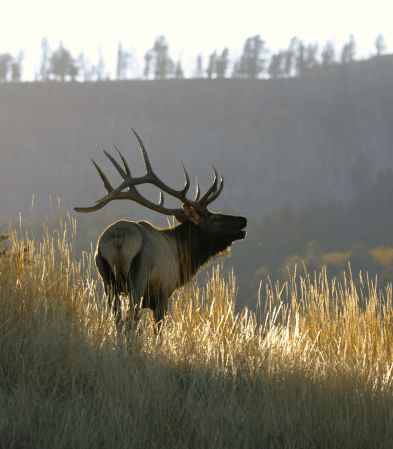

Four weeks later, I was sitting behind my spotting scope, staring at distant elk, on a preseason quest to find the big bull I would hunt with my flintlock. All I’d seen were smallish ones—beautiful animals, but not what I’d waited 17 years to hunt. Doubt began to creep in. What if I couldn’t find a big bull? What if I had to eat the tag I’d spent so long trying to acquire? But I reminded myself that I needed to enjoy this experience—that it wasn’t just about killing a huge bull.

Opening day dawned clear and still, and several bulls bugled in the distance. Working our way through ponderosa pines and scrub oak thickets, my friend Greg and I passed on a couple of small 6-points. A thin bugle floated up from a low ridge ahead. As I watched the bull push a cow through some oaks, I knew he was better than any I’d seen in a week of scouting, scoring perhaps 365 B&C. I badly wanted his massive tops and huge, curving royals. A half hour later, I botched a 30-yard encounter with the bull and inwardly gave myself a thorough cussing.

Just before nightfall, Greg and I rapidly closed the distance on an unfamiliar bugle. As we peered around a clump of scrub oaks, we could see a bull standing among his cows. He was unmistakably huge, though his tremendous antlers were difficult to resolve among the shadows. Darkness quickly took away any chance for a shot, so we backed out rapidly, working downwind and out of the bull’s space. Hiking our way back to camp in the black of night, we wondered aloud just how big the bull actually was.

MOMENT OF TRUTH

On the afternoon of the third day, a storm blew in from the west, rattling golden aspen leaves and sending them fluttering to the ground. The rumble of thunder over the far blue peaks had us straining our ears for the sounds of bulls. Finally, as the sun slipped behind the mountains, we heard bugling deep in an aspen thicket. The memory of the huge bull we’d seen two nights before spurred us into a swinging trot through the forest. It was a race against darkness.

Bulls bugled, thrashed trees, and clashed antlers. Cows dodged in semicircles, heads and necks extended, trying to escape the attention of the frenzied males. We recklessly closed the distance and struggled to identify the herd bull through the rippling mass of elk. Several 330-class bulls moved through the timber in front of us. The herd bull bugled, and Greg and I looked at each other in silent agreement: It was the voice of the bull from two nights prior.

Failing light drove us to creep closer to the herd—my iron sights would soon be ineffective. A huge form moved around the herd toward us. Now we were within 100 yards. My brother, who had joined us that morning, watched through his binocular, his excitement palpable. I peered through my own glasses to assess the bull but immediately dropped them to my chest so that I could raise the long barrel of my flintlock. My sights blurred in the dim light as the bull stood broadside at 65 yards, a sliver of his vitals showing through the timber. As the sights slowly came into focus I squeezed the trigger, sending a flash of fire and smoke into the dusk and a round ball into the bull’s heart and lungs. He staggered 30 yards and fell with a tremendous crash.

A TRADITIONAL CELEBRATION

It was the most incredible celebration of a harvest I’ve ever experienced. He was a massive, dark-antlered 7-by-8, and we all knew he had to be pushing 400 inches. We stood with our arms locked around each other and screamed with exuberance into the darkening sky. Then we knelt around the bull and gave a prayer of thanks for this blessing, muffled sniffling accompanying our words of gratitude.

We photographed the elk and the rifle, then set about our work of harvesting the bounty of meat. Thunder crashed and the front wave of a storm blotted the stars from the sky. Carrying packs laden with treasure from the high country, we turned into the storm and were instantly drenched. Lightning provided blinding glimpses of frothing rain and bowing treetops as we descended the mountain to the safety of my truck.

When I tell people the stories of last season’s adventures, they typically respond with genuine admiration for my use of traditional equipment. In a world where technology pervades everything we do, hunts like mine are increasingly unusual. I’m not averse to using modern rifles, magnified scopes, rangefinders, and GPS, but I’m proud that I chose to use a longbow and a flintlock on these hunts. The fact that I achieved perfect one-shot kills on both animals pays tribute to the effectiveness of my primitive armament.

My bull green-scored 404 2/8, and after drying, it grosses 402 inches and nets 385 1/8 non-typical, placing it Number 18 overall in the Longhunter Society’s record book. It ranks as the biggest bull ever recorded as harvested with a flintlock.

Formed in 1988 by the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association, the Longhunter Society is like the Boone and Crockett Club, but for muzzleloaders only. Bringing recognition to those hunters who accept the challenge of using muzzleloading firearms and honoring trophy animals harvested with the same, the society also actively works to support conservation of all North American wildlife.

The first Longhunter Society Big Game Record Book was published in 1992. Several updated editions have followed and serve as permanent archives of trophy-class big-game animals taken with muzzleloaders. Unfortunately (to my way of thinking, anyway), there is no distinction made between traditional and modern muzzleloaders. Be that as it may, the society provides a valuable service to those of us who love muzzleloaders and the wildlife that we pursue with them.

Illustrations by James Carey, photos courtesy of the author.