We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn More ›

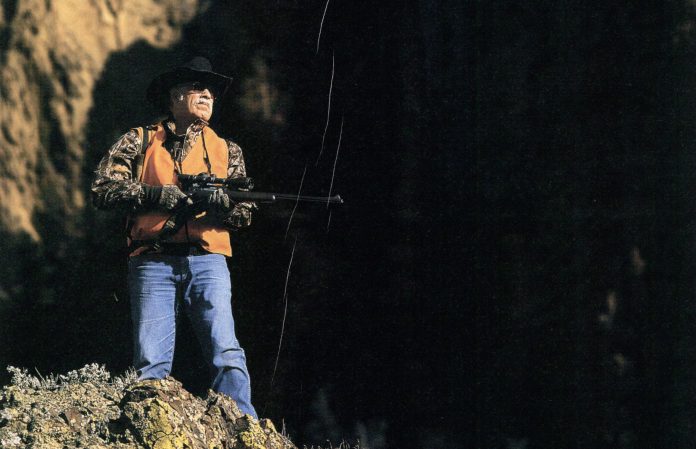

Larry Ness, a collector from Yankton, South Dakota, spent five decades assembling a carefully curated collection that tracks the development of firearms from the earliest days of western expansion by American settlers to the dawn of the 20th century. One of the most storied rifles in his possession was a Winchester Model 1876 chambered in .45/75 WCF that belonged to the famed Lakota Sioux chief Sitting Bull. Ness had many other significant historic firearms acquired that included rifles used in the Battle of Little Big Horn, like a Model 1873 Trapdoor Carbine and Relic Colt 1873 single-action.

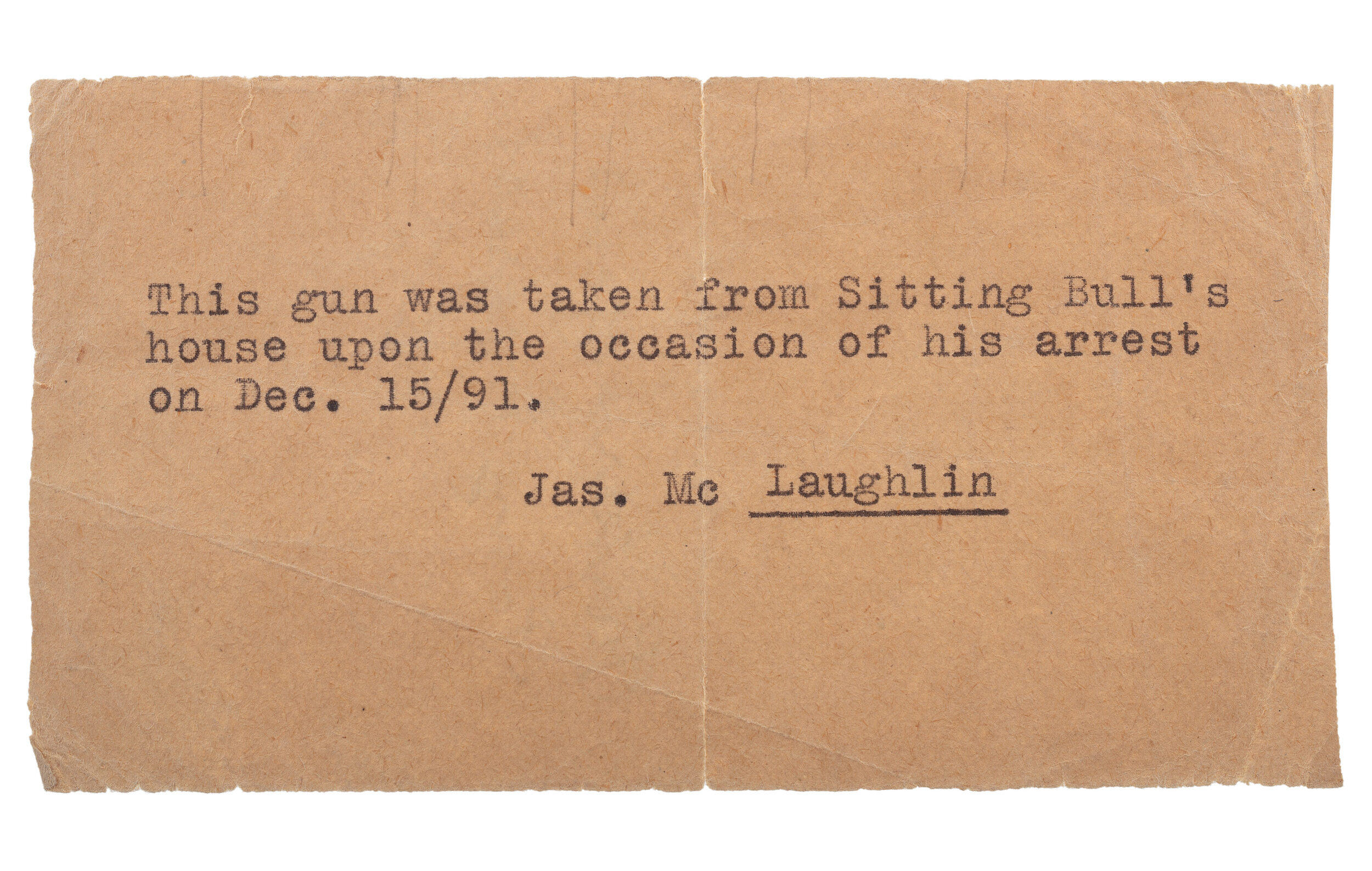

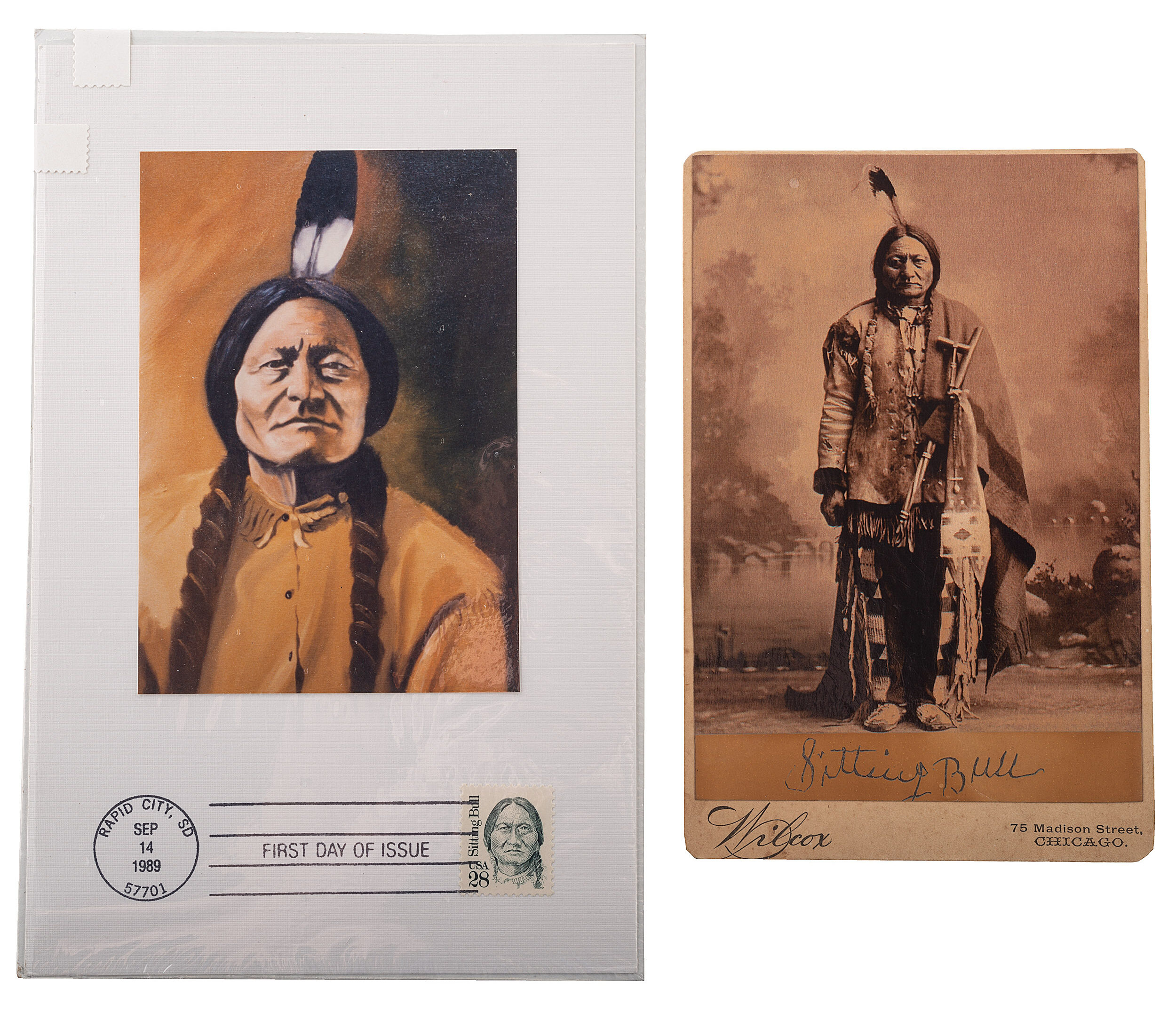

On June 8, Cowan’s Auctions will auction off the Winchester lever gun that belonged to Sitting Bull—along with many others—in one of the largest and most complete collections of Native American related firearms. Sitting Bull’s Winchester comes with extensive documentation supporting the attribution to the Sioux chief (1831-1890). The rifle was supposedly recovered from Sitting Bull’s cabin on the day he was killed (December 15, 1890) during a botched arrest attempt by U.S. Indian Police. The Model 1876 was turned in to Standing Rock Reservation Indian Agent Major James McLaughlin (1842-1923), who subsequently became the first owner of Sitting Bull’s rifle.

Sitting Bull’s Winchester Model 1876

The Winchester Model 1876 lever action rifle was also known as the “Centennial Rifle” because it was made for the U.S. Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The rifle is a larger framed version of the Model 1873. The gun was chambered for several calibers—.40/60 WCF, .45/60 WCF, or .50/95 WCF—and offered in 22-, 26-, or 28-inch barrel lengths. Sitting Bull’s is chambered in .45/75 WCF. It was made around 1877 and features a 28-inch octagonal barrel with full magazine.

It has a blued finish with color case-hardened hammer and lever. The 1876 has a is straight-gripped walnut stock with crescent buttplate and smooth fore-end. The barrel is marked in two lines forward of the rear sight: “WINCHESTERS-REPEATING-ARMS NEW HAVEN, CT/KING’S-IMPROVEMENT-PATENTED-MARCH 29, 1866. OCTOBER 16, 1860.” The upper receiver tang is marked “MODEL 1876.” The open top frame is without a dust cover or rail. Based on the serial number, this gun would have been made at the very end of the 1st Model “open top” Model 1876 production. It has a trapdoor in the buttstock for cleaning rods, which are not present.

The condition of the 1876 is good considering its age. The metal has a moderately oxidized plum patina mixed with gray, which shows some evenly scattered surface roughness and pitting. And the barrel markings have some wear. While it is mechanically functional, the poor bore is dark, dirty, and heavily oxidized with weak rifling. The wood is lightly sanded with moderate wear and the fore-end has chips and loss along the upper edge and is somewhat loose on the frame. There is a diagonal crack on the obverse running from the nose cap. There are scattered bumps, dings, and mars as would be expected with a rifle this old.

Before being acquired by the current owner, the 1876 was sold by Christie’s in 2000, Little John’s Auction Service in 2000, and then sold by Julia’s Auctions in 2015. The firearm estimated to be sold somewhere between $40,000 and $60,000.

The Guns of Sitting Bull

Historical records indicate several firearms were removed from Sitting Bull’s cabin at the time of his death and were turned in to, or later acquired by McLaughlin. One of McLaughlin’s personal notebooks identifies “Guns turned in and captured by Indian Police subsequent to Dec. 15th 1890” including three identified directly to Sitting Bull.

Additional evidence corroborates that after Sitting Bull’s death at least one gun, along with other items once belonging to him were sold or given by McLaughlin to individuals associated with collecting Native American ephemera and Western Americana. In a letter written by McLaughlin on April 30, 1891, to D.F. Barry, a 19-century photographer well known for his work with the Lakota people, including portraits of Sitting Bull, McLaughlin indicates that he presented Barry a “Sharp’s” carbine for his collection of “Curios.” McLaughlin adds that the rifle “was one of five rifles found in Sitting Bull’s house by the Police” on the morning of December 15, 1890.

A June 14, 1897, letter published in Rudolf Cronau’s article My Visit Among the Hostile Indians and How They Became My Friends from South Dakota Historical Collections, Vol. XXII, offers evidence that a Mr. W.D. Campbell, owner of Campbell’s Curio Store in Los Angeles, California, had also obtained articles once owned by Sitting Bull “from the Indian agent at Standing Rock and he [agent James McLaughlin] got them when [Sitting] Bull was killed.”

Sitting Bull: A Brief Biography

When he was born, the future Native American leader was named “Jumping Badger,” but as he grew acquired the nickname “Slow,” referring to his cautious and deliberate personality that kept him from rushing into things. At age 14, he participated in his first war party, where he counted his first coup and was subsequently bestowed with a new name by his father, “Thathanka Iyotake,” meaning “Buffalo Who Sits Down” in Lakota. This name was corrupted by the English language to “Sitting Bull.”

His first major combat action against the U.S. military came in 1864, when an army retaliatory strike over the 1862 Dakota Uprising led to an attack on the village in which Sitting Bull lived. During that battle the defense of the camp was coordinated by Sitting Bull and Lakota leaders Inkpaduta and Gall. Later that year Sitting Bull led a small band of about 100 warriors in a skirmish with U.S. soldiers that resulted in the leader being shot through the hip, although the wound was not serious.

Sitting Bull supported the Oglala leader Red Cloud during his war against the U.S. from 1866 to 1868, leading warriors and fighting in several engagements during that conflict. At the conclusion of the war, Red Cloud and several other leaders signed the treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, but Sitting Bull refused to sign. This period began his adamant stand against the signing of treaties and the ceding of Native lands to the U.S. government. He was steadfastly opposed to the concept of reservation life and the reliance upon the government for the subsidies that would feed Native people on the reservation.

Sitting Bull soon became the titular leader of not only the Hunkpapa Lakota but of most of the Sioux and Cheyenne bands that refused to submit to life on the reservation, and essentially became the poster child for Native American resistance on the plains. His standing as a leader among the Native peoples of the plains, both politically and spiritually, continued to increase during the first half of the 1870s. With the discovery of gold in the Black Hills and the subsequent U.S. military expedition led by Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer in 1874 to further assess the mineral values in that region, the pressure for the Sioux and Cheyenne to resist these new incursions into territory that had been guaranteed to them by the Fort Laramie Treaty mounted.

In 1875 many of these non-reservation bands gathered for a large Sun Dance at which Sitting Bull had his famous vision regarding a future major military victory over the U.S. Army. This vision would come to fruition on June 25, 1876, when Sitting Bull’s camp of combined Sioux and Cheyenne were attacked by Custer’s 7th Cavalry. The attack was authorized by a February 1, 1876, decree from the U.S. Interior Department that classified all the Native Americans living off the various reservations on the plains as hostiles, who were to be treated accordingly. Although Sitting Bull would not directly participate in the battle, leaving the leading of the men to younger war leaders like Crazy Horse, his overall leadership of the people prior to the event as well as his vision regarding the victory is often considered pivotal to the Native American success that day.

Sitting Bull in the Aftermath of the Little Bighorn

In the wake of Custer’s defeat at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull led a band of followers into Canada to evade the onslaught of U.S. retaliatory strikes that he knew would be coming. The situation in Canada was brutal for his people. In 1881, after many of his followers had already abandoned harsh conditions and near starvation, Sitting Bull led his remaining band of 186 family members and followers to surrender at Fort Buford, Dakota Territory. In 1883 Sitting Bull and his band were transferred to the Standing Rock Reservation and came under Federal supervision of James McLaughlin, Indian Agent. The following year western show promoter Alvarez Allen took Sitting Bull on a tour of some areas in Canada and the U.S., and during this time Sitting Bull met the famous trick shooter Annie Oakley. The two developed a friendship. The following year, Sitting Bull joined Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show and toured for several months, giving much of the money he earned away to the poor.

As discontent with the corruption of the reservation system became more widespread among Native Americans, a new religion appeared that provided hope to the forlorn. The “Ghost Dance Movement” was steeped in the Christian concept of peace, universal love, and the return of the Messiah, but more importantly preached the return of dead native ancestors, the return of the buffalo, and an end to the western push of the white man. The tenants of the belief also stated that the donning of special ceremonial clothing, most notably the “Ghost Shirt” would make the wearer proof against bullets. While a purely peaceful movement, the dances and rituals associated with the ceremonial part of the religion scared many U.S. leaders, who conflated the ceremonies with war dances.

At Standing Rock, Indian Agent McLaughlin was especially worried. Fearing a general uprising, he ordered the arrest of Sitting Bull who he felt was in some way involved or behind the new religion. On December 15, 1890, Indian Police Lt. Bullhead led a group of officers to arrest Sitting Bull. Sitting Bull refused to comply with the order to come with the police and a group of his supporters gathered to help protect him. When the supporters indicated that they were willing to use force to prevent the arrest, Bullhead shot Sitting Bull in the chest causing a wound that would eventually lead to his death later that day. Following the shooting of the Sioux leader, a melee ensued leaving several dead and wounded on both sides, including Lt. Bullhead. It was after this tragic event that McLaughlin purportedly removed several items from the Sitting Bull cabin, no doubt understanding their future value as souvenirs of the great leader.

Was Millionaire Parker Lyons the First Collector to Own Sitting Bull’s Winchester?

In the early 1900s few men in America were more recognized for their collections of Western Americana than W. Parker Lyon (1865-1949). A successful businessman with a larger-than-life persona, Lyon was a multi-millionaire. Accounts vary, but Lyon likely started seriously collecting between 1910 to 1915 after his move to San Marino, California. By the 1930s, his collection is believed to have consisted of more than a million Western artifacts including a railroad depot, a Wells Fargo office, a western saloon, a sheriff’s office, stagecoaches, wagons, Pony Express ephemera, saddles, and an extensive firearms display that included the guns of Billy the Kid, Buffalo Bill Cody, and Black Bart.

Considering that Lyon’s Pony Express Museum housed one of the most extensive collections of Western Americana in the country, it is conceivable that at some point he would have sought to acquire one of Sitting Bull’s rifles. However, the exact scenario for Lyon’s association with the gun remains unclear. Potentially Lyon acquired the rifle directly from McLaughlin sometime between 1910-1923, during which time Lyon was beginning to grow his collection and McLaughlin was still in the Indian service.

Alternatively, the gun could have some connection with the Sitting Bull items that were originally part of W.D. Campbell’s collection. Campbell’s collection was in Southern California before he sold it in the late 1890s and, while portions of that collection including Sitting Bull relics are known to have gone to a San Francisco collector, it is possible that other parts remained in or near Los Angeles where they were acquired by Lyon.

Read Next: Guns of the West: 10 Iconic Firearms and the Legendary Men (and Women) Who Shot Them

Post Parker Lyon History of the Winchester

The history of Sitting Bull’s 1876 from 1932 to present day is well-documented. The rifle was acquired by attorney Walter H. Robinson in 1932 at the liquidation of the Bank of West Hollywood. Robinson writes in an undated typewritten letter to noted antique firearms dealer Mr. Robert Abels: “This rifle had been left at one of the banks as security for a loan which was never paid and was purchased by me on closing up the bank’s affairs. The item was enclosed in a box showing that it had been expressed from Sitting Bull’s neighborhood in Dakota in which box it is still enclosed.”

Parker Whedon of Charlotte, North Carolina, purchased the rifle from Robinson’s widow, Mrs. Edith Jones (Robinson) Roush in 1965. In an affidavit of November 1965 provided by Robinson’s widow to Whedon, she testified that the rifle was brought by her late husband to their home. Whedon later conducted extensive research of his own into the provenance of the rifle, and portions of his correspondence are included with the documentation. Among those documents are a 1968 affidavit from Chief William Red Fox of the Oglala Tribe of the Sioux Nation who testified that he was “well acquainted with Chief Sitting Bull of the Hunkpapa Tribe of the Sioux Nation.”

Chief Red Fox’s affidavit further attested that after carefully examining the Model 1876 Winchester serial number 3536 it was in his opinion “an authentic ‘Indian’ rifle of the kind in general use by the Sioux in the Dakotas during the 1880s and was owned and used by a master warrior or Chief of the Sioux Nation. I do not doubt that this was the rifle taken from Sitting Bull’s cabin at the time of his death.” Parker Whedon owned the gun for several more decades until it was auctioned by Christie’s in July of 2000. The rifle was sold again in November of 2000 by Little John’s Auction Services. The gun was sold to the present owner in 2015 by James D. Julia, Inc.

Tim Prince is a senior firearms specialist at Cowan’s Auctions. Historical information in this article was also provided by the American Historic Ephemera and Photography department to delineate as accurately as possible the origin and chain of custody of Sitting Bull’s Winchester 1876.