I’m always surprised to hear mule deer described as “dumb,” particularly with respect to their whitetail cousins. While whitetails enjoy a reputation for a nearly prescient level of wariness, mule deer have gotten the rap as the class-dunces of the deer world, at least in the eyes of some.

Having stalked a good number of mule deer the past couple days in mountains around Granby on the C Lazy U ranch and surrounding public lands, about the last thing I’d accuse these mule deer of is a lack of intelligence or a diminished sense of self preservation.

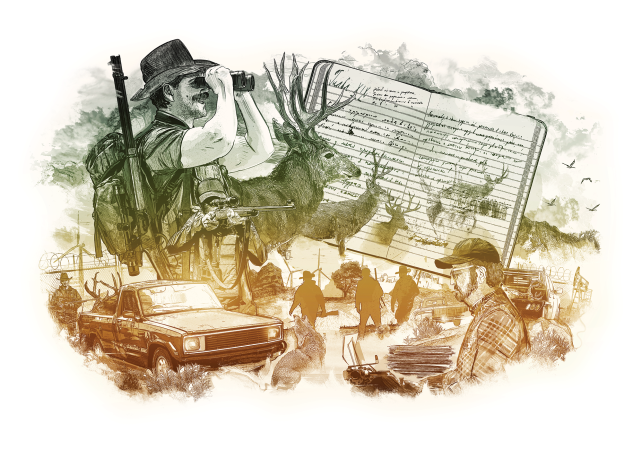

A few years back, former Outdoor Life hunting editor Jim Zumbo and I were talking about mule deer and their defenses. Jim said he felt mule deer, as a rule of thumb, have about a 600-yard comfort zone and that if you intrude within that range and aren’t careful the deer will get edgy and start to spook. That pretty much squares with my experience and seems right to me.

I went out the other day with Tyson Arnold, the younger brother of my friend Cody, who I’m hunting with here, and we decided to target this one particular drainage where some big deer had been spotted.

We got up early and made the 600-foot climb to the top of the ridge in time to see the drainage at first light. Deer were all over the hillside, which was a mixture of sage and patches of aspen and pine. The bottom of the drainage was a snarl of vegetation that the mule deer used as a water source and bedding cover.

We settled in on a small rocky knob that gave us great views to the north and south and decided to spend the day glassing the country. When we first crested the ridge, a small group of does in the bottom blew out of there and headed south. We didn’t see them again or any deer from that direction.

After an hour and a half, most of the deer we could see, which were to our north, had drifted back into the timber or located deeper sagebrush and bedded down.

Tyson and I hunkered down and waited. We were covered up very well, just our shoulders and heads peered above our protective nest of sage, and we kept quiet and still.

In the evening, deer started to reappear, but at further distances than in the morning. The closest deer were 450 yards off and even the slightest movement from our hide cause the deer, and one wary old doe in particular, to freeze and stare our way. How that tiny motion, by a camouflaged arm, could be spotted more than a quarter mile away in the gloom amazed me.

Her kin were hardly less on edge. We had been hidden and still for more than nine hours and yet we were as busted as if we had been working on a Salsa routine.

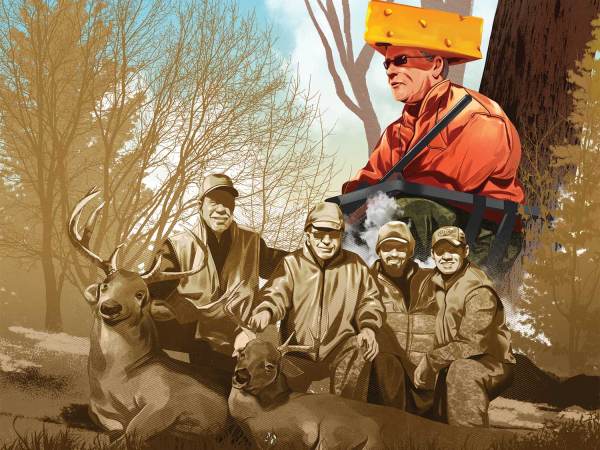

We saw one good buck that day–a solid 170-class deer–but he wasn’t the one I was looking for.

We didn’t take a deer off the mountain that day, but I did take leave with a renewed respect for those big-eared deer that would pay dividends later on.