Small towns keep secrets, dark and otherwise. Sometimes they’re not really secrets at all, just local tales and legends that fade away until they become a secondhand whisper. When the accumulated dust of time gets scratched away, the truth turns out to be a bit different from the legend. I knew that’s the way it could be with the world-record bass of Demopolis, Alabama.

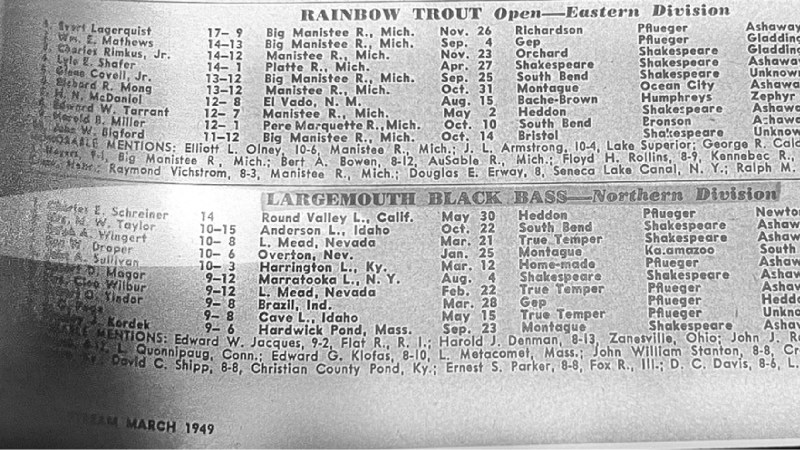

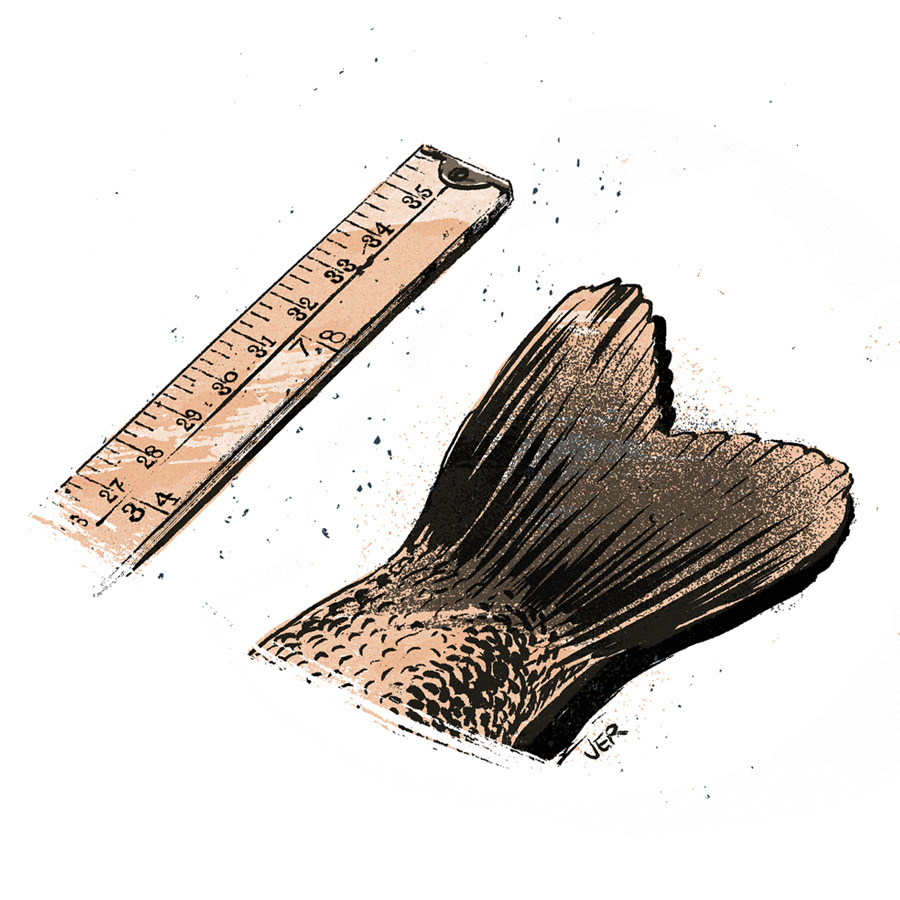

If you thought the world-record bass was caught in 1932 by George Perry in Montgomery Lake in Georgia, you’d be right, of course. While there is no verified photo of Perry with the fish nor physical remains of the granddaddy of all largemouths, it stands as the record. (It was tied in 2009 by Manabu Kurita with a 22-pound 4-ounce fish taken from Lake Biwa, Japan.) The trail to the Demopolis bass, caught in 1926, however, had long gone cold. But unlike Perry’s fish, there was a photograph of the Demopolis fish that undeniably places it in time and location, and verifies its size. It was photographed alongside a Braswell Hardware yardstick. It’s hard to know if whoever set up the photo understood the genius of that prop. Its purpose was certainly to provide scale for the photo.

The Braswell Hardware yardstick places it unmistakably in that West Alabama town on the chalk bluff banks of the Tombigbee River—or at least somewhere near it. Everyone who grew up in Demopolis during the 20th century knew Braswell Hardware, which dispensed everything from shotgun shells to plumbing supplies. Maybe the Braswell Hardware yardstick was the handiest measuring device around. Or maybe someone understood it could tell a story years later.

On the Trail

I first became aware of the fish when a pair of gentlemen who lived their entire lives in that town, Billy Traeger and John Caldwell, self-published a little book of stories about life in Demopolis during their youth and before. To call it history makes the town’s historian, Gwyn Turner, roll her eyes, half in horror and half in amusement. The two authors may have just wanted to pass on some of the tales they grew up with. The record bass, one story in their book, included a blurry reproduction of a photocopy that clearly shows the fish in all its 35-inch splendor next to the yardstick.

I remembered the story while reading Monte Burke’s Sowbelly, a tome on the quest for the world-record bass, so I emailed him. He’d heard dozens of tales like it. But could it have been true? Burke devoted significant space in his book to the debate over whether Perry’s fish existed or whether it was truly a largemouth bass. For most of my life, I had taken it on faith that Perry’s fish was undeniably the world record.

Friend and fellow writer Mike Bolton, the longtime outdoor columnist for The Birmingham News, looked at Perry’s record with a cold, clinical eye and hypothesized that the Georgian had caught a striped bass that had somehow wound up in Montgomery Lake. In his eyes, Perry’s bass simply didn’t fit the dimensions of a large, pot-bellied, Florida-strain largemouth, the only kind of bass known to grow to that size. I argued that it was likely a freakishly large northern-strain largemouth.

If I was right about the Perry bass, then couldn’t the Demopolis bass have been the same thing? Of course, the Demopolis bass would merely be a curiosity because of this tragic detail: It was likely caught in a commercial fisherman’s net by a workaday netter named John Dutton. I wanted to know more, but both John Caldwell and Billy Traeger have passed away since writing their book.

T.M. Culpepper III, a longtime businessman and highly regarded citizen, had written a more scholarly book that included the tale. At 87 years old, Culpepper lives in a tidy white cottage on North Main Avenue that overlooks the Tombigbee. North Main, with its restored Victorian homes, is a rather fashionable address in that little town today. But in Culpepper’s youth, it was just a part of town called Gritney, and there was a garbage dump at the end of the street where a park and boat landing are now. It was home to hard-working commercial fishermen and other ordinary folks.

The river Culpepper grew up with was different. Today, a lock and dam built in the 1950s elevates the pool 40 feet. Back then, navigation on the Tombigbee and Black Warrior rivers was controlled by a series of 10-foot lifts built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Culpepper remembers a river that he could wade across in dry weather, and he plied its waters in a homemade cypress skiff powered by paddles.

He tried his hand at netting fish with what he calls a hoop net he bought from Dutton’s wife, who made them. He didn’t have much luck, but he learned how it was done. And he never lost his love for the river. He sees it every day of his life and gazes out over it at sunset.

Back in the early 1950s, he went off to the University of Alabama, but the Korean War called. After he returned home, he never finished his degree, and that bugged him. In 1992, he took advantage of a program the university offered to students who wanted to complete a degree. As a final project, he collected information from old-timers for an oral history called Life on the Tombigbee River. It contains the story of the great bass.

Net Result

The newspaper clipping from The Birmingham News was accompanied by the photo. One of Bolton’s predecessors, Walton Lowery, said the photo was sent to him by a Robert L. Hudson. Dutton was fishing at Lock 3, where he had a camp downriver from Demopolis, when the big fish struck at one of the fish caught in his net and became gilled. Even then, there was a law against netting game fish, and Dutton, being an honest man, was prepared to release it. But anchored nearby was his friend, riverboat captain George Nicholls of Tuscaloosa. Lowery claimed Nicholls persuaded Dutton to give him the fish and claimed that it would never be traced back to Dutton. Nicholls had local photographer C.D. Williamson shoot the photo next to the Braswell Hardware yardstick. According to Lowery, Nicholls sent the photo to Field & Stream. But when the magazine asked him to sign an affidavit that he caught it on a rod and reel, Nicholls backed off. The magazine lost interest, and the story faded into history. The bass was allegedly consumed by the Demopolis Rotary Club, which met on Wednesdays in the dining room of The Demopolis Inn. Lowery tried to reach Dutton, who was still living at the time, but he was unable to.

“That, apparently, is the true story of the world’s biggest bass,” Lowery concluded. “That is, until Mr. Dutton can be reached. But regardless, there’s nothing fishy about Alabama’s world-record 24-pound bass.”

Well, maybe it’s a little fishy. As I sat with Culpepper on his front porch, reading one of the copies of his book, I looked at the blurry old photocopy. It was clear to me that the fish is a striped bass. A 24-pound striped bass isn’t a record. I’m pretty sure I can make out the stripes on it. A clearer picture would help. I called Dutton’s daughter-in-law, who dug through a drawer of memorabilia where she believed the actual photo was, but she couldn’t find it.

Read Next: This Man is Trying to Bring the Largemouth Bass World Record Back to the USA

I’d had some warning. Leon Null, a Demopolis old-timer of the same vintage as Culpepper, had told me, “Aw, they found out that was some old sea bass or something.” Now, looking at it, I believe that he’s right.

But it raises some questions. Why did so many people mistake it for a largemouth? Lowery quotes an unnamed friend of Nicholls as saying, “There was such a bass. He did weigh 24 pounds. And he was definitely a bigmouth.” Lowery, himself a veteran outdoor writer, doesn’t question the fish’s pedigree.

Jay Haffner, a fisheries biologist for Alabama’s Division of Wildlife and Freshwater Fisheries, just shrugs. “Back then, a bass was a bass was a bass,” he says.

Construction of bigger dams eliminated the Gulf strain of stripers from the Tombigbee. But stripers were present there back in 1926. Haffner believes anglers of that time knew little about them. Bass fishermen fished the banks with topwater plugs from boats that were paddled or sculled, usually in backwater. Striped bass lived and fed mostly in open water, where no self-respecting angler would cast his plug back in 1926. About the only fisherman likely to run across one would be a commercial fisherman like Dutton.

So, with a legend chased down and debunked, I ended my search for the world-record bass in Demopolis. And I have to wonder if my pal Mike Bolton, and others who have shared his hypothesis about Perry’s bass, might be right. But that’s another fact or legend or myth, whatever it may be, for someone else to tackle.