When they were first introduced to the national hunting community, these novel methods for bringing in bucks were considered unconventional at best, and harebrained schemes by most. Now deer hunters everywhere use these tried-and-true tactics. We take a look back in our archives to when these trusty standbys were still considered downright bizarre.

1. RATTLING

The brush-country hunters of Texas and New Mexico were crashing antlers together for decades before the trend caught fire in the rest of whitetail country. Although native hunters likely developed the technique, legend has it that an old market hunter accidentally discovered the phenomenon:

“He was coming to town one day, his wagon loaded with deer carcasses, when a buck came barging out of the mesquite. The hunter, so the story goes, added him to the load. A short time later, another buck pranced up—and was soon in the wagon. The puzzled hunter stopped to figure things out and discovered that two carcasses were lying so their antlers clashed as the wagon jounced along the rough country road.”

—Hart Stilwell, “Why Not Try to Rattle Up a Buck,” May 1951

Our first story devoted to rattling appeared in October 1937. A Texas game warden, drawing on 30 years of experience with the tactic, taught author Fredric P. Schwab exactly how to sound like “two bucks in a life-and-death struggle.”

By the 1950s, most hunters in the rest of the country had heard of rattling, but few had tried it. Almost everyone who had tried tickling tines reported the method didn’t work on hill-country deer, although a rare hunter outside the Lone-Star State would claim success.

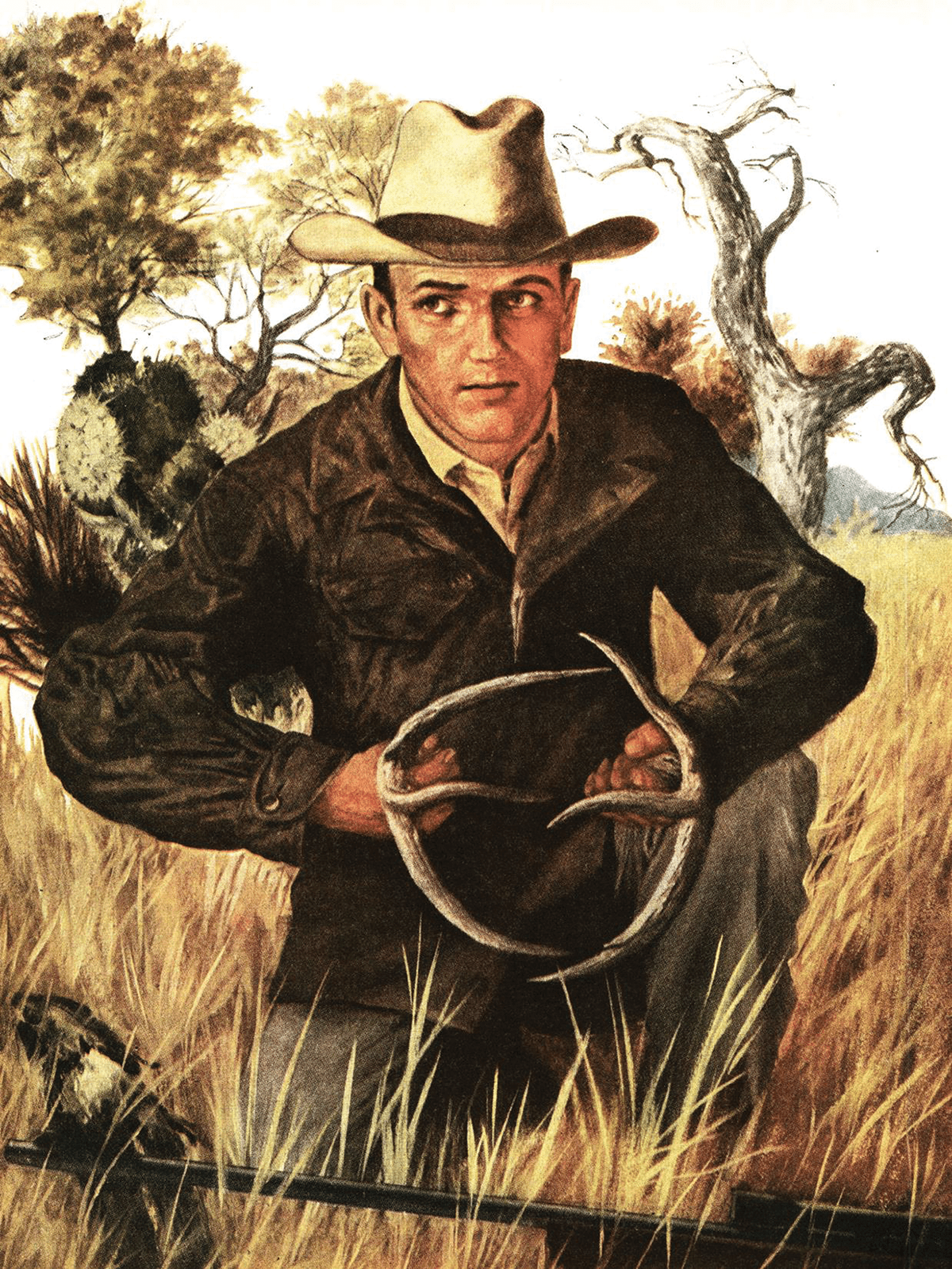

2. CALLING

The concept of calling for deer was less established even than rattling in the middle of the 20th century. In August 1949, an experienced deer hunter traveled to Alaska for a Sitka blacktail hunt. “He was sure it was just a gag,” reads the story. “Who ever head of calling a buck?”

“Now I’ve used crow calls, duck calls, and turkey calls, and I’d read that down in Texas they lure bucks by rattling a couple of antlers together. But a real deer call I’d never heard of. Probably my voice expressed my skepticism. ‘O.K. I’ll bite. What’s a deer call?’”

The Alaskan hunters employed the call often—which looks a bit like a harmonica and sounds like “a lost lamb bleating for its mother,”—but they admit they don’t know what sound it was supposed to replicate. “I’ve attracted does as well as bucks, so I don’t think it’s a mating call,” said one local. “An old Indian told me it’s the cry of a fawn in mortal terror,” said another.

In the end, the author and a fellow hunter call in two bucks and drop both of them. This story, “A Deer Call Brings ‘Em In!” garnered so much reader mail that an advice column on using commercial calls appeared in the October 1949 issue. The expert claimed to have used his call with excellent results on 100 wild deer, and that his call was a modern counterpart of those made by Native Americans in Alaska. So while calls were being produced commercially by the late 40s, they remained news to most hunters.

3. SCENTS

Although a variety of products designed to lure bucks and cover up human odor had been marketed for years, it appears most hunters initially considered the scents for sale at the local sporting goods shop akin to something hawked by a snake oil salesman.

“It was probably because I was growing desperate that I decided to buy the deer scent,” writes John Weiss, author of the November 1978 feature “Scents and Nonscents.” “I figured there was nothing to lose.”

Weiss reported that more than 50 companies made scents at the time, and were raking in an estimated $37 million a year. That included everything from hunter’s soaps and food attractants to tarsal scents and urine.

He then delved into the types of scents and their effectiveness, and dug into the “scientific” realm of deer hunting. Interestingly, most biologists interviewed for the story disregarded “a deer’s scenting ability as not all that important.” One researcher noted that a deer’s “visual capabilities are far more refined than hearing or smelling abilities.”

Yet most wildlife biologists today agree that a deer’s nose is it’s most formidable asset. Nonscents, indeed.

It makes you wonder: If these are the facts we believed back then, just think about what we’ve got wrong now. And, even more fun to imagine, is what “crazy” tactic might be all the rage in another couple decades.