The hottest argument in bowhunting these days revolves around heavy, slow arrow setups versus faster, lighter arrow setups. One of the sticking points in this discussion is the whitetail deer’s ability to “jump the string.” Many bowhunters believe that shooting a faster bow means that a deer will have less time to duck which results in better hits and quicker kills. However, a growing group of bowhunters is opting for heavy arrows which are designed for penetration, not speed. Their logic is that no bow can beat a whitetail’s reaction time, so an arrow that penetrates deeper will give the bowhunter more room for error when a deer does duck or spin (since a heavier arrow is more likely to push through bone).

Both perspectives come from the right place. After all, we all want the most effective setup to make the most ethical kills. But amid this discussion, and within all the content published around it, there have been some less-than-scientific conclusions.

To cut through the hyperbole, I interviewed two expert bowhunters—Aaron Warbritton of The Hunting Public and Michael Hunsucker of Heartland Bowhunter—who combined have each reviewed video footage of hundreds of archery shots made on deer. By reviewing their shots (and their buddies’ shots) in slow motion, they are able to see exactly how deer react. Combined, they’ve killed huge old bucks, average-sized bucks, and all varieties of does in states across the country on pressured public land and exclusive private ground—all on camera. The sheer volume of their experiences provides valuable insight to all bowhunters.

Jumping the String, Explained

But first, let’s get our terminology straight. Jumping the string means the deer hears the bow release, or the arrow whizzing toward it, and instinctively ducks down to load its legs before springing off. But deer can also react by spinning, dodging away from the noise, or a little bit of both. Despite the term, deer rarely “jump” up in the air. Think of it more as a deer “jumping the gun” than actually jumping.

Whitetail deer in particular are known for ducking the string so effectively that their reaction impacts where the arrow hits. At farther ranges, it can even cause flat-out misses. If you’ve made many archery shots on whitetails, you’ve likely experienced this yourself. Sometimes even shots that feel absolutely perfect end up hitting off the mark, this is often because the deer ducked at the shot.

The Math: Can Fast Bows Beat a Deer’s Reaction?

One of Warbritton’s biggest takeaways from reviewing hundreds of shots from The Hunting Public’s footage and from his earlier days at Midwest Whitetail is that ducking starts to become a problem at a range from 25 yards to 35 yards. This is regardless of whether the hunter is shooting a speed bow or slow bow. Inside 25 yards, and especially inside 20 yards, ducking becomes less problematic with either setup, Warbritton says.

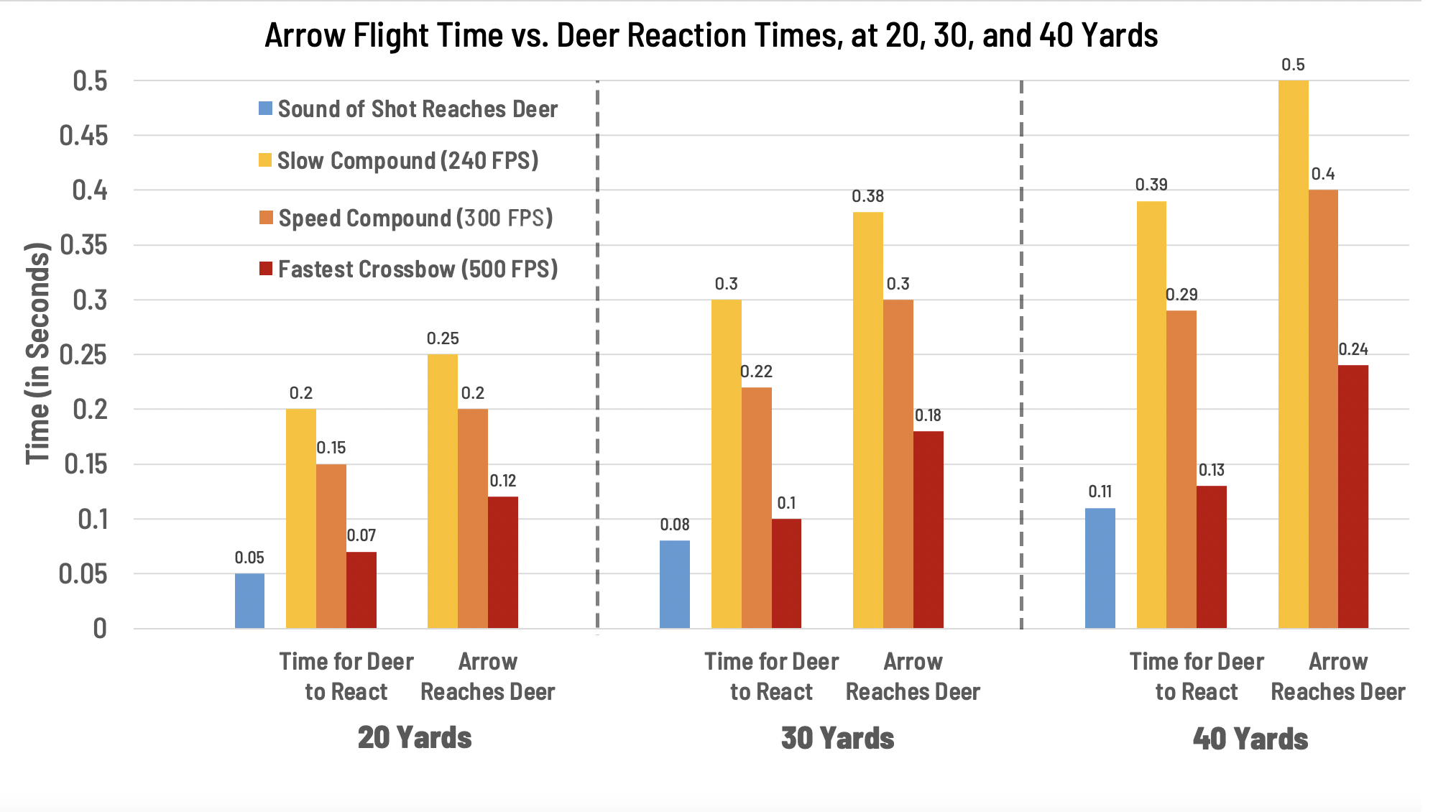

I decided to apply some math to Warbritton’s observations. In the chart below you’ll see results for the amount of time deer have to react to a shot at different yardages for different speeds. Keep in mind that the speed for each bow is the average speed across the range, since the arrow slows as it travels. So, for example, the “Slow Bow” setup shooting 240 fps, would likely read 250 fps out of a chronograph. The 300 fps “Speed Bow” would be cranking out arrows at about 310 FPS at the point blank. The superfast crossbow speed of 500 fps is based on the fastest crossbow in the world, the Tenpoint Nitro 505, which we chronographed in our review of the best crossbows of 2022 at 515 fps.

There are two other important factors here: The speed of sound and a deer’s reaction time. The speed of sound is about 1,125 fps. There are a lot of opinions out there about a deer’s reaction time. For reference, elite sprinters have a reaction time of just under .15 seconds. In Olympic track, any start within .10 seconds of the gun is considered a false start. (You can see the reaction times of sprinters from the 2016 Rio Olympics here). Based on slow-motion video evidence, it’s safe to say that deer can react more quickly than even the fastest humans.

Based on the data above, it’s clear that speed bows have an advantage at 30 yards and beyond, not so much at 20 yards and in. But even the speed bows are too slow to fully beat a deer’s reaction time at 30 and 40 yards.

On the flip side, it’d be nearly impossible for a deer to duck the fastest crossbow, even at 40 yards. But for crossbow hunters using average crossbows, which generally shoot 350 fps to 400 fps, string ducking could be an issue at 40 yards and beyond.

A note on bow speeds: Bow manufacturers advertise bow speeds based on industry specifications that are unrealistic for most bowhunters’ setups. Most compound bowhunters will be shooting between 300 fps and 250 fps with their hunting rigs. See the actual chronographed speeds of the best compound bows of 2022 here.

Years ago, whitetail guru Grant Woods did an experiment comparing bow speed vs. the speed of an object falling (he used water balloons). Based on this experiment, he estimated that a deer could duck two inches at a 20-yard shot, 6 inches at 30-yard shot, and 10+ inches at 40 yards. These findings seem to jive with the basic math in the chart above.

The Problem with the Math

Based on this math, bowhunters could simply calculate their arrow speed, calculate reaction time and drop, and then adjust for a lower hold at any given range. But here’s the problem: Deer aren’t water balloons. They’re individual animals that all respond in different ways under different circumstances and there’s no way to predict how a deer is going to react at the shot, Warbritton says.

“Their reactions are so dynamic and different in every situation that you cannot predict what the deer is going to do,” Warbritton says. “Over all the video we’ve watched, we noticed that some deer would duck straight down to the ground. Some deer would drop a foot at 30 yards. Some would drop four inches at 30 yards. Some would not move at 30 yards. Some would duck and roll away. So, they would be broadside at 30 yards, duck six inches roll away and by the time the arrow impacted, the deer is actually quartering away instead of broadside.”

For example, Warbritton references a hunt in Arkansas where he shot at a doe and had it duck the string completely. The same doe came back into range, Warbritton shot again, and this time the doe barely ducked at all (even though it had already been shot at). This shows that even the same deer can react differently.

Warbritton’s solution to this has been to keep shots as close as possible, and that’s been a general theme for the THP crew. Over their most recent 40 archery kills, the average shot distance has been 16.5 yards.

“You can’t beat the deer once you get beyond 20 yards, so optimize your setup for 20 yards and be extremely mindful when you’re taking shots beyond that,” Warbritton says. The video below shows a hunt from years ago in which Warbritton was shooting a speed bow and made a bad hit on a buck at 30 yards because it ducked and spun at the shot. In recent years, he’s gotten even more stringent about taking close shots.

This year Warbritton is shooting two different arrow setups, both on the heavier end of the spectrum: one 700-grain arrow with a 200-grain single-bevel broadhead for close-quarters woods hunting and one 500-grain arrow with a 150-grain broadhead for Western whitetail hunting. He’s overly not concerned about his arrow speed with either setup.

Field Experience Trumps All

Hunsucker has also seen hundreds of slow-motion video shots on whitetails—he typically shoots between 15 to 20 deer with his bow each season—and he agrees there’s no way to predict how a deer is going to react. His main takeaway is that experience and confidence are much more important than your gear. For reference, Hunsucker shoots an arrow with a 95-grain insert and 100-grain expandable broadhead, which gives him a total arrow weight of 500 grains. He isn’t overly concerned about the speed of his bow.

He’s much more concerned about reading all the right information before taking a shot. When a deer comes into your setup, you need to analyze a ton of information all at once, he says. This includes the shot distance, the deer’s body position, its body language and mood, other deer around it, the deer’s front leg position, ambient noise conditions, and the shot angle.

“Confidence is everything,” Hunsucker says. “Being mentally aware of everything in those moments of truth pays more dividends than any sort of gear setup or rules around a decision making process.”

The simple truth is that you have to shoot a bunch of deer with a bow to get good at it. Practicing on targets certainly helps. And there are ways you can try to replicate the experience of shooting in the field (shooting in competitions will help). But nothing is as good as the real thing, Hunsucker says. So if you haven’t killed many deer with a bow, find an area that has an overpopulation of deer and punch some doe tags. If you’re an experienced archer who has made some bad hits on deer recently, think back to those shots and see what you can remember about them. If you can’t recall those specific details mentioned above, and the whole shot process felt like a blur, then you weren’t taking in all the necessary information in the moment.

“For me it’s more about being able to harness the emotion during the heat of the moment than it is about being the world’s best target shooter,” Hunsucker says. “Thinking back to my early years of bowhunting most of [the mistakes] came from not being aware of the whole situation.”

Thoughts on Aiming Low

Whitetail hunting expert Bill Winke has done a lot of work around string-jumping whitetails over the years. His solution has been to simply aim lower the farther the shot.

But ultimately, where to aim comes down to personal experience and there’s no perfect formula to it. Generally speaking, both Warbritton and Hunsucker will aim lower on deer that seem super twitchy, but neither advocate for aiming below the deer completely. When shooting from the ground, Hunsucker typically holds for the heart. From a treestand you must factor in the downward angle of the shot.

“[Where to aim] all varies depending on stand height and shot distance,” Hunsucker says.

Hitting too low, and behind the heart, can result in a lost deer just as easily as hitting too high.

“I’ve seen a lot of deer bumped and lost from hits that were behind the heart and below the lungs,” Hunsucker says. “People will see that shot in the moment and think ‘heart shot’ but if that deer’s front leg is back, they’re not hitting the heart, they’re hitting six inches behind it. So that’s just a diaphragm shot or liver if you’re lucky. Those deer can live and if you bump ’em it’s a very difficult track.”

Observations on String Jumping

Even though deer are completely unpredictable, there are some general observations that both Hunsucker and Warbritton have made over the years. These aren’t rules to live by, just generalizations from the field.

- Big animals duck less. Small Southern deer and twitchy does generally duck more.

- Rutting bucks that are distracted by does duck less.

- Ambient noise matters. Windy days with blowing leaves and grasses generally means less ducking than dead-quiet days.

- The vast majority of whitetails do duck or react to the shot in some way—upward of 80 to 90 percent.

- Stopping deer for a shot does promote ducking. Ideally, let the deer stop on its own or stop it as softly as possible (Hunsucker likes to start with a squirrel noise). But some rutting bucks will require a loud bleat to stop.

- Depending on the conditions, ducking is most problematic from 25 to 40 yards. At long ranges whitetails seem to react less to the shot. But for both Warbritton and Hunsucker, the vast majority of their whitetail shots are taken at 30 yards and in.

READ NEXT: Best Broadheads for Deer

Final Thoughts on String Jumping

If you were hoping for a magic formula to solve all your string jumping woes, you’re probably disappointed by now. Warbritton’s best advice is to get deer as close as possible to minimize string ducking issues. Hang stands for shots 20 yards and in. If there’s no good tree, look for a setup on the ground. Take the risk of spooking deer at close range instead of risking a farther shot and a wounded buck.

Hunsucker’s best advice is to be patient after the shot if you don’t see the deer go down or hear it crash down. Always err on the side of waiting before following a blood trail.

Both hunters say that shot placement they’ve noticed in real-time doesn’t always match up with what they see in camera footage. In other words, most bowhunters are not great at knowing exactly where they hit a deer. And sometimes the shot placement seen in slow-motion footage even differs from what they find after recovering the deer. So even when the shot feels good, treat it like a marginal hit if you can’t confirm the deer went down.